- Introduction

- Moral Philosophy: A Definition

- Conclusion

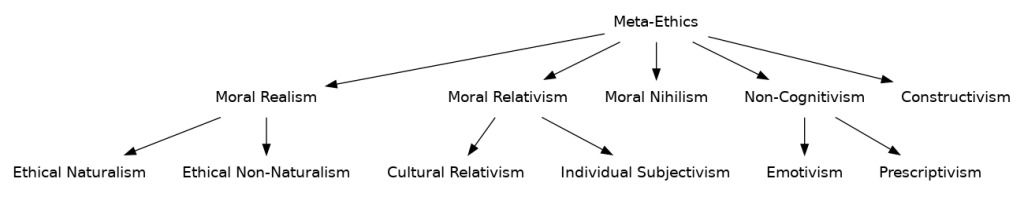

When people ask me about Morality in the age of AI, specially making blatant statements about what is considered right or wrong, I usually show them this. I cannot remember the source of this table or if it was compiled over time in my endless notes, but it serves me as a reminder of how complicated it might get to answer the, usually perceived as simple, question of defining an action or behaviour as moral/ethical or not.

Ethics (Moral Philosophy)

├── 1 Meta-Ethics ← What is morality?

│ ├── 1.1 Moral Realism / Objective Morality

│ │ ├── 1.1.1 Naturalistic Realism (Moral Naturalism)

│ │ ├── 1.1.2 Non-Naturalistic Realism

│ │ ├── 1.1.3 Theistic Moral Realism

│ │ └── 1.1.4 Value-Pluralism / Plural Realism

│ ├── 1.2 Moral Anti-Realism

│ │ ├── 1.2.1 Non-Cognitivism

│ │ │ ├── Emotivism

│ │ │ ├── Expressivism / Quasi-Realism

│ │ │ └── Prescriptivism (Hare)

│ │ ├── 1.2.2 Cognitivist Anti-Realism

│ │ │ └── Error Theory (Mackie)

│ │ └── 1.2.3 Subjectivism / Relativism

│ │ ├── Individual Subjectivism

│ │ └── Cultural Relativism

│ ├── 1.3 Moral Constructivism

│ └── 1.4 Moral Skepticism (suspension of judgement)

│

├── 2 Normative Ethics ← Which principles make actions right or wrong?

│ ├── 2.1 Deontological Theories (duty-centred)

│ │ ├── 2.1.1 Divine Command Theory

│ │ │ ├── 2.1.1.1 Strong / Voluntarist

│ │ │ ├── 2.1.1.2 Modified (Loving-God) Version

│ │ │ └── 2.1.1.3 Intellectualist / Co-extensive Version

│ │ ├── 2.1.2 Kantian Deontology

│ │ ├── 2.1.3 Rossian Plural Duties

│ │ └── 2.1.4 Natural-Law Ethics

│ ├── 2.2 Consequentialist Theories (outcome-centred)

│ │ ├── 2.2.1 Utilitarianism

│ │ │ ├── Classical (Hedonistic)

│ │ │ ├── Preference

│ │ │ ├── Act

│ │ │ └── Rule

│ │ ├── 2.2.2 Negative Utilitarianism

│ │ ├── 2.2.3 Agent-Relative Teleological (Ethical Egoism)

│ │ └── 2.2.4 Ideal-Observer Theory

│ ├── 2.3 Virtue Ethics (character-centred)

│ │ ├── Aristotelian

│ │ ├── Stoic

│ │ ├── Confucian

│ │ ├── Thomistic

│ │ └── Buddhist

│ ├── 2.4 Contractualism / Contractarianism

│ │ ├── Hobbesian Contractarianism

│ │ └── Scanlonian Contractualism

│ ├── 2.5 Ethics of Care

│ ├── 2.6 Pragmatist / Pragmatic Ethics

│ ├── 2.7 Moral Particularism

│ └── 2.8 Pluralistic / Hybrid Theories

│

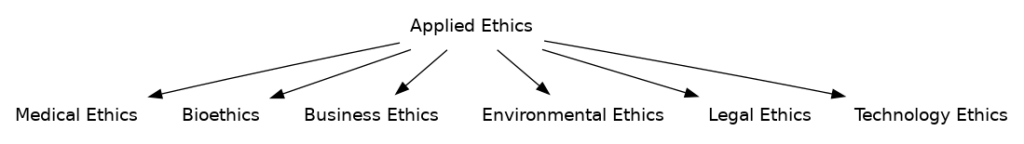

└── 3 Applied Ethics ← How do those principles guide real-world issues?

├── 3.1 Biomedical & Health-Care Ethics

│ ├── Clinical Ethics

│ └── Research Ethics

├── 3.2 Environmental Ethics

│ ├── Deep Ecology

│ └── Ecofeminism

├── 3.3 Animal Ethics

├── 3.4 Professional & Business Ethics

│ ├── Accounting / Finance Ethics

│ ├── Marketing Ethics

│ └── Engineering, Legal, Journalism Ethics

├── 3.5 Technology & AI Ethics

├── 3.6 Media & Communication Ethics

├── 3.7 Legal & Criminal-Justice Ethics

├── 3.8 Political Ethics & Public Policy

├── 3.9 Military Ethics & Just-War Theory

├── 3.10 Gender, Sexuality & Family Ethics

└── 3.11 Sports & Entertainment EthicsNotice there is nothing here that mentions AI, yet, except in one branch. Unfortunately though, we cannot understand that branch until we have established a strong understanding of the overarching branches and schools, if nothing else, then at least for the sake of comparison.

Introduction

What is morality, and how should we think about ethical decisions? These age-old questions form the basis of moral philosophy (also known as ethics). Moral philosophy provides a framework for understanding right and wrong – a foundation that is increasingly crucial in the age of artificial intelligence. As AI systems become more advanced and integrated into society, developers and users alike must grapple with ethical questions: How should an autonomous car make life-and-death decisions? Should an AI assistant follow all instructions it’s given? By exploring moral philosophy, we equip ourselves with concepts and principles to thoughtfully address such questions. This introductory post sets the stage by mapping out the major branches of moral philosophy and defining key terms. Understanding these branches will give AI practitioners and general readers a common language and toolkit for the ethical discussions to come.

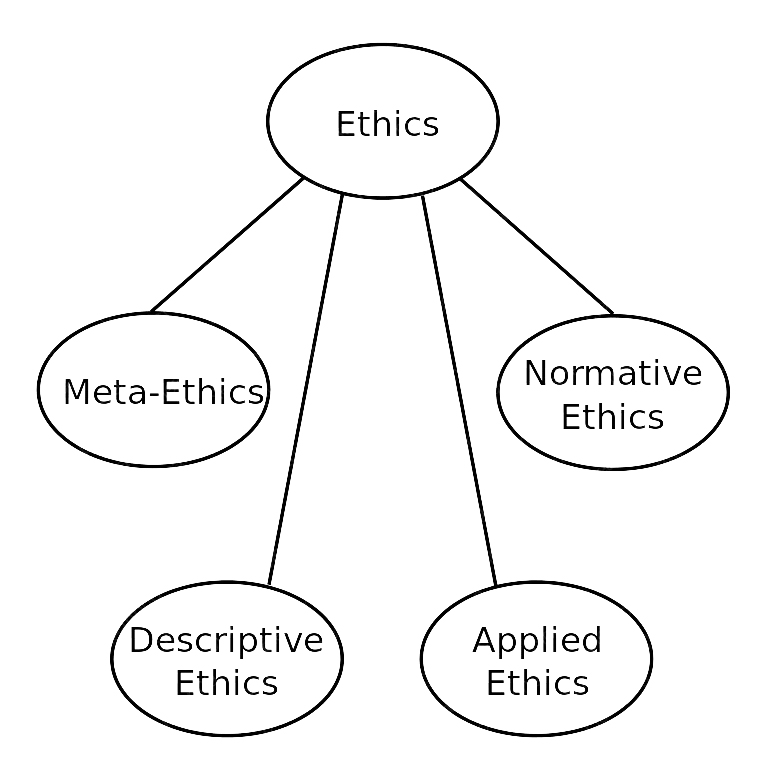

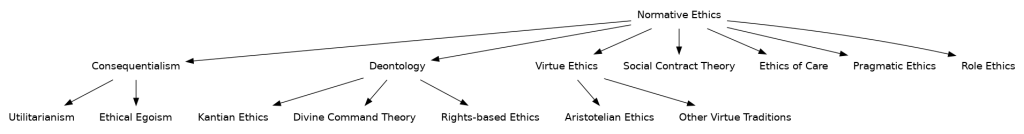

An illustrative “ethics tree” diagram showing the main branches of ethics. Classical moral philosophy is commonly divided into Meta-Ethics, Normative Ethics, and Applied Ethics (with Descriptive Ethics sometimes identified as a separate branch focusing on how people actually behave). Each branch of the ethics tree addresses a different dimension of moral inquiry, as outlined below.

Moral Philosophy: A Definition

Moral philosophy, or ethics, is the branch of philosophy that examines questions of right and wrong, good and evil, virtue and vice. It asks “How ought we to live, and why?” Ethics is traditionally divided into three broad domains: meta-ethics, normative ethics, and applied ethics. Each of these domains contains numerous sub-branches and theories, creating an expansive “moral philosophy tree” of ideas. In this paper, we explore every major branch and sub-branch of that tree, following a structured breakdown of categories and subcategories. The discussion is organized into three main sections corresponding to the three domains. Each section defines the domain, then elaborates on each sub-branch in detail with definitions, key ideas, and practical examples.

Meta-Ethics

Meta-ethics is the foundation of moral philosophy, concerned not with what actions are right or wrong, but with more abstract questions about morality itself. It examines the meaning of moral language, the nature of moral facts or values, and how (or if) we can know moral truths. In other words, while normative ethics and applied ethics deal with what is moral, meta-ethics asks what morality is. For example, if two people disagree on whether an action is ethical, meta-ethics steps back and asks: What do we mean by “ethical”? Are there objective facts about right and wrong, or are moral values subjective? How can we justify or know any moral claim? Meta-ethical inquiry is highly abstract and often called “second-order” moral theorizing (since it analyzes the assumptions behind our first-order ethical judgments).

Key questions in meta-ethics include:

- Meaning: What do words like .“good,” “wrong,” or “duty” really mean? When someone says “Kindness is good,” are they stating a fact, expressing a feeling, or something else?

- Ontology: Do moral properties (like goodness or wrongness) exist independently out in the world? Are they part of reality (like physical properties), or are they human creations, or illusions?

- Epistemology: If moral truths exist, how can we know them? Through reason, intuition, divine revelation, or cultural consensus?

- Psychology and motivation: Why do moral judgments influence our behavior? Does saying “Stealing is wrong” carry any motivation by itself, or do we need a desire to be moral for it to matter?

Meta-ethical theories offer differing answers. The major branches of meta-ethics can be mapped according to two primary axes:

- Moral Objectivity: Are there objective moral facts (true regardless of human opinion)? The moral realism vs. anti-realism debate centers on this. Moral realists say yes, there are objective truths about right and wrong. Anti-realists say no, morality is not objectively factual in that way (it may be subjective, relative, or entirely fictitious).

- Cognitive Meaning: Do moral statements express truth-apt beliefs that can be true or false, or do they express non-factual attitudes? This is the divide between cognitivism (moral language expresses beliefs/propositions) and non-cognitivism (moral language expresses feelings, commands, or attitudes, not truth-claims).

Using these distinctions, we can outline the sub-branches of meta-ethics as follows:

Moral Realism (Moral Objectivism)

Moral realism holds that there are objective moral facts or truths – moral values exist independently of our beliefs or perceptions. In this view, when we say “Honesty is good” or “Murder is wrong,” we are describing real features of the world (not just our opinions). A moral realist believes statements like “Charity is morally right” can be true or false in an objective sense, much as statements about the natural world can be true or false. Moral realism is often associated with moral objectivism, the idea that some moral principles hold universally, for everyone.

However, moral realists differ on what exactly these objective moral facts are and how they exist. Two important sub-branches of moral realism are ethical naturalism and ethical non-naturalism.

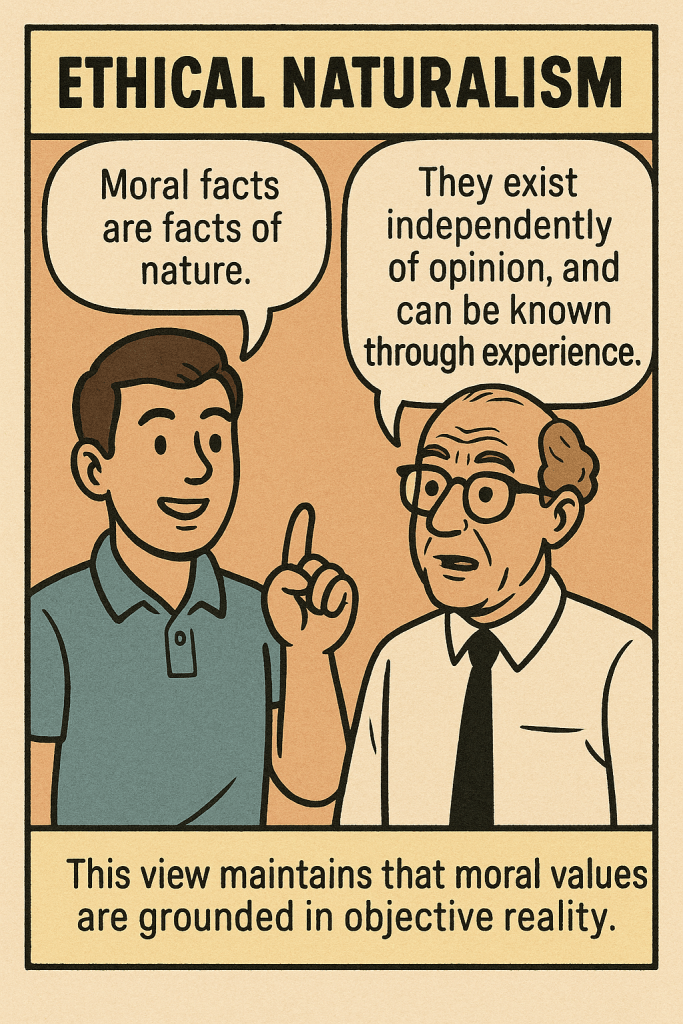

Ethical Naturalism

Ethical naturalism (or moral naturalism) is the realist view that moral facts are essentially natural facts – part of the natural world and accessible through empirical observation or science. In other words, moral properties like “good” or “evil” are reducible to or constituted by natural properties (such as pleasure or pain, human flourishing, preferences, biological needs, etc.). Moral truths can thus be studied and known in largely the same ways we discover scientific truths. For example, a naturalist might say “Goodness is just whatever promotes human well-being” – defining the moral in terms of a natural quality (health, happiness, survival, etc.). If so, one could investigate empirically which actions increase well-being to determine what is morally right.

This position treats ethics as continuous with science and reason. Many ethical naturalists argue that moral judgments can be verified or confirmed by evidence (for instance, data about what causes happiness or social stability). Classical utilitarianism is often considered a form of naturalism: it equates “good” with pleasure or happiness (a natural psychological state) and uses observation (of consequences) to judge right actions. Aristotelian virtue ethics can also be seen as naturalistic in grounding virtue in human nature and what causes humans to flourish. Modern thinkers have even proposed a “science of morality” to empirically understand how to maximize wellbeing.

Example (Ethical Naturalism): A naturalist might argue that kindness is morally good because it tends to increase overall social cooperation and personal happiness (observable outcomes). Since these outcomes benefit human well-being – a natural fact – kindness derives its moral value from that natural property. Thus, “Kindness is good” could be tested by studying its effects on communities.

One challenge to ethical naturalism is G.E. Moore’s Open Question Argument (1903). Moore pointed out that no matter how you define “good” in natural terms (say, as “pleasure”), it always remains an open, meaningful question: “Yes, pleasure is nice, but is pleasure really good?” The fact that such a question makes sense suggests that “good” might not be reducible to any specific natural property – implying a gap between facts and values. This critique led Moore and others to favor non-naturalism.

Ethical Non-Naturalism

Ethical non-naturalism is the realist stance that moral facts are real and objective, but not reducible to natural facts. On this view, moral properties are a unique kind of thing – irreducible and perhaps knowable through intuition or rational insight rather than observation. Non-naturalists often consider moral truths as abstract, more like mathematical truths or Plato’s Forms: real in a philosophically robust sense, but not physical. For example, a non-naturalist might say “Justice” or “goodness” are fundamental aspects of reality, not identifiable with any empirical phenomenon, but nonetheless objectively existing.

Philosopher G.E. Moore himself argued that “Good” is a simple, indefinable quality – we can’t break it down into natural terms without a loss of meaning. This view is sometimes called moral Platonism or intuitionism: moral knowledge comes via rational intuition of self-evident truths. Early 20th-century intuitionists (Moore, W.D. Ross) held that we directly “see” certain acts as right or wrong by a kind of moral insight, just as we might grasp a mathematical axiom. These truths (e.g. “Hurting others for no reason is wrong”) don’t derive from natural science, but we recognize them as objectively valid.

Non-naturalist moral realism emphasizes the sui generis (of its own kind) nature of ethics. Moral facts exist, but they are special – not observable like gravity, yet not mere subjective opinions. This position can appeal to those who feel morality has a weighty, universal authority that can’t be explained away as just natural preference. However, it faces the challenge of explaining what moral facts are if not natural, and how we access them. Critics have called non-natural properties “queer” or ontologically strange, raising what philosopher J.L. Mackie termed the “argument from queerness” against objective values.

Example (Ethical Non-Naturalism): A non-naturalist might argue that courage is a virtue in and of itself, not because of any measurable outcomes it produces, but because we intuitively recognize the value of bravery. Even if an act of courage leads to negative consequences, we might still honor it as morally good – suggesting the goodness lies in the act’s character (an abstract quality), not in empirical results.

Theistic Moral Realism: Some moral realists (like me) ground moral facts in a divine source – for instance, God’s commands or nature. If one believes God’s will defines objective morality, then moral truths exist independently of human minds (in God’s mind or character). This can be seen as a form of moral realism (moral facts are real because God guarantees them). It overlaps with normative Divine Command Theory , but at the meta-ethical level it asserts an ontological foundation: “Good” exists as an aspect of God or as ordained by God. This raises its own puzzles (see the Euthyphro dilemma: Is something good because God commands it, or does God command it because it is good?). Theistic realists typically answer that God’s perfectly good nature defines goodness objectively.

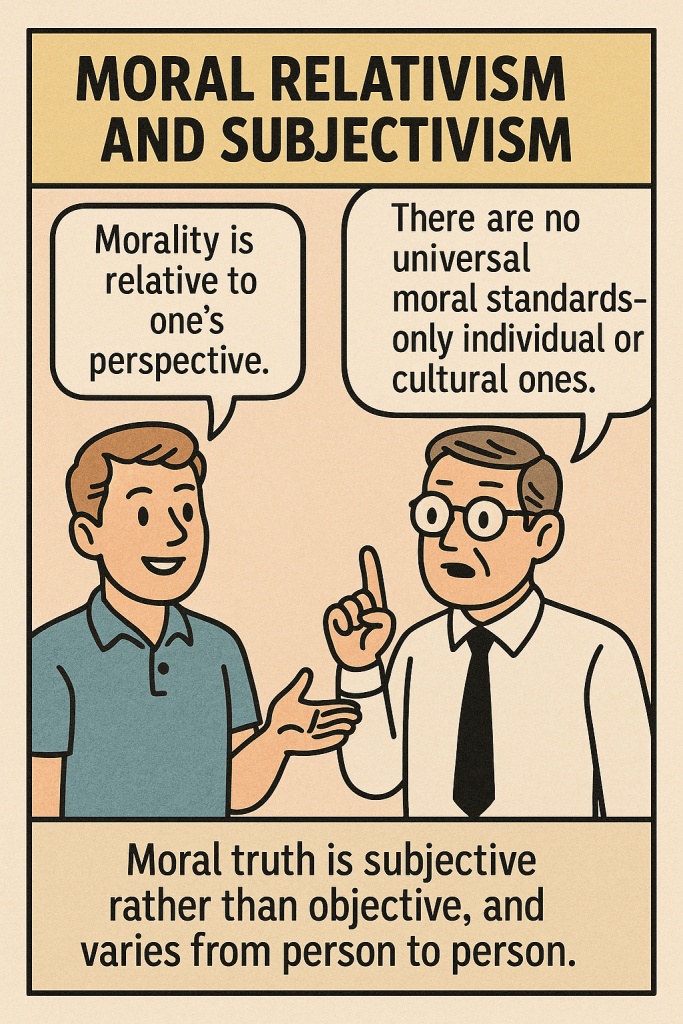

Moral Relativism and Subjectivism

On the opposite side of realism stands moral anti-realism, which encompasses several views that deny objective, independent moral facts. Foremost among these are moral relativism and moral subjectivism. These theories hold that morality is human-dependent – created by human minds, societies, or cultures – rather than an external truth. According to relativists and subjectivists, moral judgments can be true or false only relative to some standpoint (a culture, society, historical period, or individual), and there is no uniquely correct standpoint that overrides all others. In short, morality is a human construct.

- Moral relativism usually refers to cultural relativism: the idea that what is morally right or wrong depends on the norms, values, or beliefs of a particular culture or society. There are no universally valid moral principles, only culturally bounded ones. For example, a practice deemed wrong in one society (say, polygamy or alcohol consumption) might be morally permissible in another; and there is no objective fact of the matter beyond those social standards. Moral truth is relative to culture: an action is right for a society if it coheres with that society’s moral framework. Relativists often emphasize the anthropological observation that different societies have radically different moral codes, and they argue we should avoid ethnocentric judgment. They also contend that no culture’s values are objectively superior – we have to judge each practice within its context.

- Moral subjectivism is a closely related position at the individual level: it holds that morality is ultimately a matter of personal attitudes or opinions. A moral claim like “Charity is good” simply means “I approve of charity” or “My values endorse charity.” There is no fact of the matter beyond individuals’ sentiments. In subjectivism, each person in effect has their own moral truth. This view implies that when individuals disagree morally, they’re not debating an objective truth but merely expressing different personal standpoints. (For example, if Alice says lying is wrong and Bob says it’s not always wrong, each is stating their own stance; neither is “objectively” correct or incorrect.)

In practice, “moral relativism” is often used broadly to cover both cultural and individual dependency of morality. The core idea is that moral standards are not absolute: they are created by humans and can vary. Relativists typically deny that any moral principle (even basic ones against harm or dishonesty) holds universally for all people at all times. They also argue that tolerance of other cultures’ values is a virtue, since without objective truth, we should avoid condemning moral practices that differ from our own.

Example (Cultural Relativism): In Society A, eating animals might be considered morally wrong due to religious belief in the sanctity of all life. In Society B, eating animals is morally acceptable and part of traditional cuisine. A cultural relativist would say there is no absolute moral rule about eating animals – it is wrong in Society A (according to A’s standards) but not wrong in Society B (according to B’s standards). And we, observing from outside, cannot declare one society “correct” and the other “mistaken” morally, since each is right by its own moral framework.

Example (Subjectivism): An individual subjectivist might say “Generosity is good means nothing more than I like generosity.” If another person says “I think generosity is foolish,” then generosity is “good” for the first person and “not good” for the second, and that’s the end of it. Moral discourse becomes a description of personal preferences, not a search for universal truths.

Under moral relativism/subjectivism, moral disagreements are often seen as ultimately unresolvable by reason, because each party may just be coming from a different framework. This has led critics to charge relativism with promoting a problematic tolerance for “anything goes.” If every culture’s or person’s values are equally valid, does that mean we cannot criticize horrific practices (like slavery or genocide) in other societies as wrong? Relativists respond that they can still object on grounds of their own values, but they acknowledge no Archimedean point outside all value systems from which to pronounce final judgment. Some relativists (e.g. philosopher David Wong) attempt to find a middle path: recognizing a plurality of moral values that are grounded in human nature broadly (so not an anything-goes free-for-all), yet allowing that different societies rightfully prioritize different values within some constraints.

It’s worth noting that meta-ethical relativism as described here is a claim about truth of moral judgments (they have truth relative to standards). This is different from merely describing that people’s beliefs differ (that’s descriptive cultural relativism, a sociological fact). Meta-ethical relativism asserts no independent moral facts beyond those relative standards.

Moral Nihilism (Error Theory)

Moral nihilism is an even more radical form of moral anti-realism. The term “nihilism” implies a belief in “nothing” (nihil). In ethics, moral nihilism is the view that there are no moral truths at all – no right or wrong, no good or evil, in any objective sense. If moral relativists say “moral truth exists, but it’s relative to standpoints,” nihilists go further to say no standpoint makes moral statements true, because morality itself is a kind of fiction or illusion. All moral claims are, at best, false statements (since they purport to describe a non-existent moral reality) or meaningless expressions with no truth value.

A leading form of moral nihilism is error theory, championed by philosopher J.L. Mackie. Error theory is so named because it says that all moral judgments are in error: whenever people make moral claims (“It’s wrong to cheat,” “We ought to help the poor”), they are talking as if there were objective moral facts – but since no such facts exist, all those claims are systematically false. According to Mackie, our ordinary moral discourse presupposes objectivity (we behave as if some actions really have the property of wrongness), and thus we’re always committing an error in judgment, attributing properties that nothing actually has.

In simpler terms, the error theorist agrees with the moral realist that moral language aims at stating truths, but asserts that no moral statement is ever true, because the world contains no moral features to make them true. This position combines cognitivism (moral statements do express propositions) with a stark form of anti-realism (all those propositions are false). It’s akin to saying: moral discourse is like talk about phlogiston or witches – people might earnestly discuss them, but those referents simply aren’t real, so all such statements are false or ungrounded.

Another variant of nihilism is sometimes called moral fictionalism – the idea that while moral claims aren’t true, it might be useful to engage in moral talk as a convenient fiction (some philosophers explore this as a way to live with nihilism without throwing out moral practice entirely).

Moral nihilism in practice: A nihilist would contend that saying “Murder is wrong” is not stating a truth, since “wrongness” doesn’t objectively exist. It’s as if one said “Murder is gloob” – if “gloob” is a non-existent property, the sentence has no truth. A committed nihilist might still dislike murder or prevent it, but they wouldn’t claim any moral fact makes murder wrong (they might cite practical or emotional reasons instead). In the extreme, a nihilist could conclude that since nothing is truly right or wrong, any action is permissible – though in reality many nihilists personally adhere to ethical codes for non-moral reasons (like preferences or social contracts).

Moral nihilism can sound alarming – the idea that “morality does not exist” – and it faces strong opposition. Critics argue that nihilism cannot account for the deeply felt experience of moral obligation or the interpersonal function of morality. If truly nothing mattered, why live or act at all? Nihilists respond that one can live by subjective values, or that morality might simply be a human invention (useful or not). Some also point out that nihilism doesn’t necessarily lead to immoral behavior – a person could disbelieve in objective morality yet decide to act kindly out of personal desire or aesthetic choice, rather than duty.

Nonetheless, the specter of “anything goes” often haunts discussions of nihilism. Without belief in any moral facts, what stops someone from doing awful things? Philosophically, nihilism remains a challenge: it asks whether all our moralizing is built on a grand illusion. Mackie, for instance, argued we have objective reasons to reject belief in objective values (such as their “queer” metaphysical nature and the observation of cultural variability). Thus, he concluded, it’s more plausible that our moral assertions are all false than that there exist objective values of the extraordinary type required.

In summary, moral nihilism/error theory represents the denial of morality’s reality. It is a minority view (most philosophers try to salvage some form of moral truth or at least function), but it is important as a consistent position that tests the assumptions of all others.

Reality Check: It’s worth noting that even among anti-realists, not all embrace full nihilism. Some (like relativists or subjectivists) believe moral claims can still be “true” relative to a person or culture. And non-cognitivists (next section) avoid error theory by saying moral statements aren’t even in the business of truth – thus they can’t be false if they’re not truth-apt to begin with. Nihilism remains the harshest meta-ethical verdict: the entire moral enterprise lacks truth or foundation. As one summary puts it, moral nihilism holds that moral judgments have no objective validity or truth-value – morality, therefore, does not exist in any real sense.

Moral Non-Cognitivism (Emotivism and Prescriptivism)

So far, we’ve considered theories (realism, relativism, nihilism) that generally agree moral statements purport to describe facts – they just disagree on what facts exist. Now we turn to non-cognitivist theories, which take a different approach: they claim that moral language does not even attempt to state truths. In other words, when we make moral statements, we are not expressing beliefs that can be true or false (thus non-cognitive), but rather doing something else – like venting emotions, issuing commands, or prescribing behavior.

Under non-cognitivism, the whole question of moral truth is misplaced, because moral sentences “lack truth-values” by their very nature. This perspective emerged in the 20th century with the rise of logical positivism and analytic philosophy’s focus on language. If moral statements aren’t factual claims, then disagreements in morals are not clashes of beliefs but perhaps conflicts of attitudes or imperatives.

Two classic non-cognitivist theories are emotivism and prescriptivism:

Emotivism (the “Boo/Hurrah” theory)

Emotivism asserts that moral judgments are expressions of emotion or attitude, not statements of fact. When you say “Stealing is wrong,” according to emotivism you are not describing stealing; you are effectively saying “Stealing – boo!” – expressing disapproval of it. Conversely, saying “Charity is good” equates to “Charity – hooray!” – cheering for it. This is why emotivism is often nicknamed the “boo/hurrah theory” of ethics.

A.J. Ayer and C.L. Stevenson were early proponents of emotivism. Ayer argued that moral language simply evinces our feelings and perhaps tries to influence others to share those feelings. Under emotivism, moral sentences are not truth-apt: they’re more like exclamations or interjections. For example, shouting “That’s wrong!” in response to a theft is akin to shouting “Boo, theft!” – an emotional exclamation of condemnation. Such utterances can’t be true or false; they just show the speaker’s attitudes (and perhaps aim to arouse similar attitudes in listeners).

Emotivism can explain why moral debates often have a persuasive, motivational aspect – we’re not just trading facts, we’re trying to influence others’ attitudes. It also fits with the observation that someone might sincerely say “X is wrong” without any evidence, purely from sentiment. According to emotivists, that’s fine because no evidence is needed for an expression of feeling.

Example (Emotivism): Take the statement “Helping a stranger in need is good.” If Alice is an emotivist, what she means by this is essentially “Helping a stranger – yay!” (an expression of approval and perhaps a recommendation: “I approve of helping; you should too!”). Bob might reply, “Letting strangers fend for themselves is good,” which on emotivism would be “Helping strangers – boo, I disapprove.” They are not factually contradicting each other, but expressing opposite attitudes. Their argument is more like a clash of cheerleading for different values than a disagreement about facts. To resolve it, they’d have to influence each other’s feelings, not point to factual evidence.

Prescriptivism

Prescriptivism, developed by R.M. Hare, proposes that moral statements are essentially imperatives or prescriptions – a kind of universalized command. According to Hare, when we say “You ought to do X,” we are not describing a fact but prescribing an action in a way that we commit to being universal (if anyone is in similar circumstances, they ought to do X too).

Thus, “Stealing is wrong” can be interpreted as “Do not steal,” said in a universal prescriptive voice – you are instructing both yourself and others not to steal. Unlike a mere personal command, a moral prescription carries a sense of generality (for anyone relevantly similar) and overriding importance. But crucially, it’s still not truth-apt; it’s more akin to advice or a rule one is laying down.

Hare’s idea was that moral language guides behavior by prescribing rather than describing. It also has a universalizability component: if I say “Lying is wrong (so I shouldn’t lie now),” I am logically committed to saying anyone in a similar situation also shouldn’t lie. This attempt to build logical consistency into moral discourse distinguishes prescriptivism from simple emotivism while maintaining non-cognitivism.

Example (Prescriptivism): If a doctor says to a medical student, “Doctors ought to respect patient confidentiality,” prescriptivism treats this as a prescription: “Any doctor, be sure to keep patient information private.” It’s like a rule or imperative: “Let all doctors respect confidentiality.” This isn’t a factual claim about doctors in the world; it’s a normative directive that the speaker endorses universally. If the student accepts it, they are adopting a commitment to act accordingly.

Implications of Non-Cognitivism: Under non-cognitivism, since moral statements aren’t truth-claims, moral disagreements are not about who’s right or wrong factually, but rather conflicts in attitude or commitments. An emotivist sees moral debate as attempting to influence others’ attitudes (“I boo X, you hooray X – can I persuade you to boo it too?”). A prescriptivist sees it as discussing which prescriptions we can will universally. These theories also elegantly explain the motivational force of morals: if saying “X is wrong” is akin to urging “Don’t do X,” it makes sense that if you sincerely utter that, you’re motivated not to do X. (This addresses the philosophical puzzle of why moral judgments motivate action – something cognitivist realists often debate via internalist vs externalist accounts.)

Non-cognitivism faces some challenges: logical problems like the Frege-Geach problem (how to account for moral statements in complex sentences and arguments if they’re not truth-apt). For instance, consider the statement: “If stealing is wrong, then encouraging your brother to steal is wrong.” In non-cognitivist terms, “Stealing is wrong” might be “Stealing, boo!” – but how do we understand an if-then construction with a non-propositional component? Non-cognitivists have worked out sophisticated responses (e.g., Simon Blackburn’s quasi-realism and Allan Gibbard’s norm-expressivism) to handle such issues, effectively mimicking truth conditions for moral language within a non-factual framework.

Another challenge is that many people intuitively feel moral judgments do aim at truth (“It’s really wrong to harm the innocent” sounds like a truth claim, not just “I dislike harming innocents”). Non-cognitivists must explain this intuition away as an aspect of how we use language (quasi-realists, for example, argue we project attitudes as if they were facts).

Quasi-Realism: As a side note, philosopher Simon Blackburn’s quasi-realism is an interesting development within non-cognitivism. It seeks to show that even if our moral statements are fundamentally expressions of attitude, we can still make sense of why we talk as if there are moral truths and even have a kind of “moral knowledge.” Quasi-realists claim we can earn the right to treat moral claims as true or false in practice, without positing objective moral facts – in effect, to have the advantages of realism without the metaphysical baggage, by understanding truth as relative to our moral attitudes under idealized conditions.

Moral Constructivism

Moral constructivism occupies something of a middle ground in meta-ethics. It agrees with anti-realism that there are no mind-independent moral truths “out there” in the world; however, it also agrees with realism (and cognitivism) that moral claims can be truth-apt and subject to rational assessment. The twist is that, according to constructivism, moral truths are “constructed” by some procedure or standpoint rather than discovered as independent facts.

In a constructivist view, morality is like a human construction project – we (either individually or collectively) construct valid moral principles through a certain process (often a rational deliberation procedure), and those principles are objectively binding given that we have committed to the process. The end result is not arbitrary: it is constrained by the procedure and by facts about human nature or reasoning. But prior to the construction, there were no moral facts.

Constructivism often comes in a Kantian flavor. For example, philosopher Immanuel Kant (as interpreted by some) can be seen as a constructivist: he argued that rational agents, through the exercise of practical reason and the requirement of universalizability (the Categorical Imperative), effectively construct the moral law. Christine Korsgaard, a modern Kantian constructivist, says that moral principles are the results of “constitutive” acts of willing by rational agents – they are not discoveries but decisions that any rational being must make to govern itself. Yet, because all rational beings share certain fundamental conditions, the constructed principles have a kind of universal force.

Another form of constructivism is found in social contract theory (overlapping with a normative theory we will discuss in section 2.4). For example, John Rawls’s approach in A Theory of Justice (1971) can be viewed as constructivist: he sets up a hypothetical fair bargaining scenario (the “veil of ignorance”) and argues that whatever principles would be agreed upon there are the just principles. Justice is not something we find in nature, but something that emerges from a fair agreement – a construction by agents who impose rules on themselves for mutual benefit. Those constructed principles (like equal basic liberties, or fair equality of opportunity) then become normative truths for that society. Rawls explicitly called his view “justice as fairness” a form of political constructivism.

Similarly, T.M. Scanlon’s contractualism (what we could hypothetically not reasonably reject) is a constructivist-like criterion for moral rightness. Rather than appeal to any independent moral order or utility calculations, Scanlon says an act is wrong if it would be disallowed by principles that no one could reasonably reject – essentially, morality comes from an idealized social agreement among equals.

Divine command theory can even be interpreted in a constructivist way: morality is constructed by God’s will or commands. That is, what is right or wrong is determined by God’s stipulation (not by God detecting independent moral facts). In the context of meta-ethics, that would mean moral truth is not independent of persons (here, the person is God), but is constructed by a perspective – albeit a divine one. Some consider this a theological subjectivism. For example, philosopher Robert Adams argues that ethical wrongness is based on disagreement with God’s loving nature/commands – thus moral facts exist (whatever a loving God commands), but they exist because of a stance (God’s). This ties into anti-realism in that without God, there’d be no moral facts; with God, there are facts but they are response-dependent on God’s attitudes.

To illustrate constructivism in a simple way: imagine morality as a game where we collectively agree on the rules. Before we agree, there are no “rules” – it’s not inherently wrong or right to do anything. But we, wanting to live together, might construct rules like “don’t harm each other” and “keep promises” because these follow from principles everyone could accept or from the very idea of treating people as equals. Once constructed, these rules become the moral facts for us. They are not arbitrary, because the construction follows rational criteria (like fairness or universalizability), and they are binding because any rational participant in our moral community would acknowledge them. They are objective given our adherence to the constructive procedure, but they are not objective in the sense of existing outside of any perspective.

Moral constructivism thus bridges subjective foundations and objective outcomes. It says, in effect, if you want to be a rational (or reasonable) agent, you must commit to certain normative standards – you “make” them true by committing to them under the proper conditions.

Example (Constructivism): Suppose we want to determine a fair principle for distributing resources in a society. A constructivist approach might have us imagine we’re choosing principles behind a veil of ignorance (not knowing our own position in society). Through that impartial reasoning process, we “construct” the principle that everyone should have equal basic opportunities. That principle wasn’t a pre-existing moral truth etched in the universe; it is the result of a construction procedure. Yet, once derived, it functions as a moral truth for that society: “Equality of opportunity is a just principle” becomes true within the constructed moral framework, and it guides action and critique of institutions.

Constructivism avoids the metaphysical “queerness” of non-natural realism (no strange entities – just humans reasoning), and it provides more normative guidance than plain relativism or nihilism (since not any construction goes – only those meeting rational criteria). However, critics question whether constructivism just collapses into either relativism (if different groups construct different morals, are they all equally valid?) or smuggles in realism (if the criteria for construction – e.g., rationality – end up yielding the same results any rational being must acknowledge, isn’t that effectively an objective truth?). Constructivists reply that their view is distinct: truths are procedural or constituted by agents, not “out there” beforehand, but also not purely subjective whim.

In summary, meta-ethical constructivism posits that moral principles are neither discovered nor arbitrary, but invented or agreed upon through a rational process. It captures a sense in which we create our moral world – but, ideally, we do so in a disciplined, reason-governed way that others could recognize as valid.

Recap of Meta-Ethics: Main Positions

- Realists say moral truths are objective facts (natural or non-natural).

- Relativists/Subjectivists say moral truth is always relative to cultural or personal frameworks (no universal truth).

- Nihilists deny any moral truth (all such claims are empty errors).

- Non-cognitivists say moral claims don’t even aim at truth but express attitudes or prescriptions.

- Constructivists say moral truths are constructed via rational procedures or agreements.

The following table provides a quick comparison of these meta-ethical positions, highlighting how they answer key questions:

| Meta-Ethical Position | Are moral statements truth-apt? | Are there objective moral facts? | Source/Nature of Moral Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moral Realism (Objectivism) | Yes (express beliefs) | Yes – objective facts exist (independent of human opinion) | Either natural facts (naturalism) or non-natural abstract facts (non-naturalism) give morality its truth. Moral claims can be true/false in the same way as factual claims about the world. |

| Moral Relativism | Yes (within context) | No universal facts – only relative ones | Moral “truth” depends on a cultural or group standpoint. True-for-this-culture versus true-for-that-culture. No stance-independent facts. |

| Moral Subjectivism | Yes (for the individual) | No universal facts – only individual ones | Moral truth is person-relative (“true for me, not for you”). Each individual’s attitudes determine right and wrong for them. |

| Moral Nihilism (Error Theory) | Yes (attempted) | No – no moral facts at all | Moral statements aim at truth but since nothing makes them true, they are all false or meaningless. Morality is an illusion/error. |

| Non-Cognitivism (Emotivism, etc.) | No – not truth-apt | No (question doesn’t apply directly) | Moral claims express feelings/commands, not facts. They don’t have truth-values. Moral language serves to influence or convey attitudes. |

| Moral Constructivism | Yes (after construction) | No pre-existing facts; constructed ones | Moral principles are products of a rational or agreed-upon procedure (e.g., rational agents would agree on X). Not objective beforehand, but attain a kind of objectivity once constructed by all rational agents. |

Normative Ethics

Normative ethics is the branch of moral philosophy concerned with moral standards and principles. It asks the question: “How should we behave? What moral duties do we have, and why?” In other words, normative ethics seeks to provide a framework or system to determine which actions (or ways of living) are morally right or wrong, and what makes them so. Where meta-ethics analyzes the meaning of “right,” normative ethics proposes criteria for rightness. It is often called prescriptive ethics because it tells us what we ought to do (as opposed to descriptive ethics, which merely reports what people do believe).

Historically, normative ethics has produced many competing theories of morality. These theories attempt to articulate fundamental moral principles – such as “maximize happiness” or “respect everyone’s rights” or “cultivate virtuous character” – that can guide our decisions and evaluate our actions. Each theory gives a different answer to the foundational question: “What makes an action right or wrong?” or “What should one value and strive for, morally?”

Before diving into individual theories, it’s useful to note three classic categories of normative ethical theory that dominate much of Western moral philosophy:

- Consequentialism – the goodness of actions is determined by their consequences or outcomes. (The ends justify the means, generally speaking.)

- Deontology – the goodness of actions is determined by adherence to duties, rules, or inherent rightness of the acts themselves, rather than outcomes. (Certain actions are right or wrong in themselves.)

- Virtue Ethics – morality is primarily about the virtues and character of the moral agent, rather than about individual acts or their outcomes. (Focus on being a good person and moral behavior will follow.)

These three approaches answer the question of moral rightness from different angles: outcome-focused, rule-focused, and character-focused. They form the core trio in most introductions to normative ethics. However, normative ethics also includes other approaches that don’t neatly fall into those three (such as contractualism, feminist care ethics, etc.), which we will cover as well, since our “expanded tree” includes them.

Each normative theory attempts to provide an “ideal litmus test of proper behavior,” in the words of one source. They seek principles that any situation can be plugged into to yield an ethical verdict. For example, a utilitarian principle might say: “Of all possible actions, the morally right one is that which produces the most overall happiness.” A deontological principle might say: “Regardless of consequences, never treat a person merely as a means to an end.” A virtue principle might say: “Act as a virtuous person would act in this situation (displaying honesty, courage, etc.).” These are simplified, but they show the flavor of normative rules.

Normative ethics is action-guiding. If meta-ethics is the theory about the theory, normative ethics is the theory about practice: it gives us norms (standards) to live by. It’s distinct from applied ethics (next section) which deals with specific practical issues. Normative ethics is more general and theoretical: it might tell you lying is always wrong, or that lying is sometimes okay if it maximizes welfare, etc., but it doesn’t specifically tell you whether this lie in a medical context or that lie in a business context is acceptable – that would be applied ethics using normative frameworks.

Normative theories often conflict with each other. Indeed, much of moral philosophy is debate between proponents of different theories. There may also be hybrid positions that try to combine elements (like rules that aim for good consequences, etc.). We will outline each major branch and sub-branch of normative ethics below, with definitions and examples.

Consequentialism

Consequentialism is the family of theories that judge **the rightness or wrongness of actions solely by their consequences. In a consequentialist view, an action is morally right if it leads to the best overall outcome (consequence), and wrong if it leads to a bad outcome, compared to the alternatives. In short, the ends justify the means – or more carefully, the morality of means is determined by how good or bad the ends are.

All consequentialist theories share this core idea, but they can differ on what counts as a “good” consequence and to whom it counts. Thus, sub-branches of consequentialism often specify:

- The Value Theory (Axiology): What outcome is to be maximized? (e.g., happiness, preference satisfaction, welfare, etc.)

- The Scope (Who Counts): Whose outcomes matter? (e.g., everyone equally, only the agent themselves, etc.)

The most famous and influential form of consequentialism is utilitarianism, which we’ll discuss first. There are also ethical egoism (where the agent’s own good is the focus) and other variants. Consequentialism is sometimes called teleological ethics (from “telos,” Greek for end or goal) because it is goal-oriented ethics.

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism is the classic form of consequentialism developed by thinkers like Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill in the 18th-19th centuries. The utilitarian principle is often summarized as: “The greatest happiness for the greatest number.” In essence, utilitarianism says an action is right if it produces the most net positive utility (usually defined as happiness or pleasure, minus suffering or pain) for all affected, compared to any alternative action. It is a universalistic and impartial theory – everyone’s happiness counts equally in the calculus, including the agent’s and others’.

Key features of utilitarianism:

- Consequence measure: Usually happiness or well-being (classical utilitarians were hedonists, equating good with pleasure and absence of pain).

- Sum total: It aggregates utility across all people. The goal is to maximize total (or average) utility.

- Impartiality: “Each to count for one, and none for more than one,” as Bentham put it. Your own joy or pain is not more important than a stranger’s, morally speaking.

- Greatest number: It seeks the outcome that benefits the most people in the most significant way. Sometimes there’s a trade-off between number of people and intensity of benefit; utilitarian calculus accounts for both by summing amounts of utility.

Example (Utilitarianism): A classic scenario: You are a bystander who can flip a switch to divert a runaway trolley from a track where it would kill five people onto another track where it would kill one person. A utilitarian reasoning would say you ought to flip the switch, because saving five lives at the cost of one life produces the best overall outcome (assuming each life saved is a great benefit). The happiness and future experiences of five people outweigh those of one, so the net utility is higher if five live and one dies, rather than vice versa. Therefore, flipping the switch is the right action for a utilitarian – despite directly causing someone’s death, the consequence in aggregate is better.

Utilitarianism can be subdivided into:

- Act utilitarianism: Evaluate each individual action by its consequences. In any given situation, you should perform the particular act that will maximize utility.

- Rule utilitarianism: Instead of evaluating individual actions, evaluate rules that, if generally followed, tend to maximize utility. Then follow those rules. This variant arose to handle some criticisms of act utilitarianism (like issues of trust or rights). For example, a rule utilitarian might say, “Although lying in this case might have good results, generally adopting a rule permitting lies would decrease trust and overall utility, so one should follow the rule of truth-telling.”

Variants of utility (the good to maximize) also exist:

- Hedonic utilitarianism: maximize pleasure and minimize pain (Bentham’s original idea quantified pleasures by intensity and duration).

- Eudaimonic utilitarianism: maximize happiness or fulfillment in a richer sense (Mill distinguished higher and lower pleasures, valuing intellectual and moral pleasures more highly than base pleasures).

- Preference utilitarianism: maximize satisfaction of preferences or desires (even if it doesn’t yield “felt” happiness – this approach, associated with some modern utilitarians like Peter Singer, respects what people want rather than only what gives them pleasurable sensations).

- Negative utilitarianism: minimize suffering (give priority to reducing pain over increasing pleasure).

Despite internal refinements, utilitarianism consistently demands an impartial maximizing mindset: one should always do what brings about the best aggregate outcome.

Utilitarianism has significant appeal because it aligns with intuitive ideas of promoting welfare and preventing harm. It’s straightforward and action-guiding: calculate outcomes, pick the best one. It also has a certain scientific flavor, like a moral arithmetic. And it has been influential beyond philosophy (e.g., in economics or public policy, cost-benefit analysis is a utilitarian approach).

However, utilitarianism also faces classic criticisms:

- It can conflict with individual rights or justice. For instance, a strict act utilitarian might condone punishing an innocent person if it somehow placates a mob and prevents greater harm to others (because the outcome of punishing one innocent might be better than riots harming many). This seems unjust despite the net utility.

- It demands possibly extreme sacrifice: If the goal is always to maximize total happiness, individuals seemingly have a duty to give away most of their resources to those who benefit more, etc. Critics say utilitarianism is too demanding because practically every moment you could be doing something more beneficial for others.

- Interpersonal comparison and calculation difficulties: how do you measure and sum happiness precisely? How to compare one person’s intense pain vs. many people’s mild gains? Utilitarians try to answer these via hedonic calculus or informed preferences, but it remains tricky.

- The “ends justify the means” can permit intuitively immoral acts if the outcome is good enough (lying, stealing, even killing might be justified in some scenarios by utilitarian logic). Many find that counter to moral common sense or integrity.

Modern utilitarians have developed sophisticated responses (e.g., rule utilitarianism or two-level utilitarianism where one usually follows rules but can revert to calculation in emergencies, etc.), but the tension with deontological intuitions remains a central debate.

Ethical Egoism

Ethical egoism is another type of consequentialist theory, but it differs sharply from utilitarianism on whose welfare counts. Egoism holds that each individual morally ought to act in whatever way maximizes their own self-interest or well-being (perhaps in the long run). It is consequentialist in that it looks at outcomes, but agent-relative in that the morally relevant outcome is the agent’s own good, not the good of all.

In ethical egoism, something is right for someone to do if it benefits them (or at least does less harm to them than alternatives). Unlike psychological egoism (the descriptive claim that people naturally act out of self-interest), ethical egoism is a normative stance: even if you could act altruistically, you shouldn’t, unless it somehow serves you. It’s sometimes encapsulated as “look out for number one” as a moral directive.

There are different flavors:

- Individual ethical egoism: “Everyone should act in my self-interest.” (This is a bit paradoxical as a universal doctrine, so it’s rarely advocated in that direct form.)

- Universal (or personal) ethical egoism: “Each person should act in their own self-interest.” This is the usual form: a universal rule that each agent is to maximize their own good.

Ethical egoists argue that this doesn’t necessarily mean being cruel or not helping others – sometimes helping others or following moral norms can be in your own best interest (for reputation, cooperation benefits, etc.). But the ultimate reason for action, they claim, should always boil down to it’s good for you.

Example (Ethical Egoism): Imagine you’re considering donating a significant sum of money to charity. A utilitarian might say do it if it helps more people and produces more happiness overall. An ethical egoist would say you should donate only if doing so somehow benefits you – perhaps it makes you feel good, or improves your community in ways you’ll enjoy, or avoids guilt that would bother you, or maybe the tax break is worth it. If donating would leave you significantly less happy (with no commensurate personal gain), the egoist would say you have no moral obligation to donate – in fact, you should not sacrifice your own interests substantially for others. On the flip side, if volunteering at a soup kitchen actually brings you personal satisfaction and recognition you value, an egoist could approve of it (because it serves your interests).

Ethical egoism is sometimes associated with philosophies like Ayn Rand’s Objectivism, which praised rational self-interest and saw the pursuit of one’s own happiness as the highest moral purpose. Rand argued that altruism (placing others’ needs above one’s own) is destructive and contrary to human flourishing. In her view, justice means you should neither sacrifice yourself to others nor others to yourself.

Critics of egoism contend that it fails as a moral theory because it cannot resolve conflicts of interest in a fair way, and it seems to condone harmful actions as long as the agent benefits. For example, if it’s in my interest to lie or cheat, egoism appears to say I should do so (unless getting caught harms me more, etc.). Egoism also violates a key impartiality intuition that morality requires – it arbitrarily values one person (the self) above all others. Many ethicists consider morality essentially about regulating interactions fairly or considering others, whereas egoism collapses into just doing what you want.

There is also the problem of public advocacy: if each person should pursue their own interest, should an egoist want others to become egoists? If others act selfishly too, that might impede the egoist’s own interests. Some have noted that egoism as a universal doctrine can be self-defeating (if everyone is selfish, you might be worse off than if people cooperate altruistically). Egoists reply that rational self-interest often includes cooperation, but it’s cooperation for mutual gain, not out of altruism – “enlightened” self-interest.

It’s worth mentioning psychological egoism vs. ethical egoism: psychological egoism is a descriptive theory claiming people always act for their own interests (even seeming altruism is motivated by some self-regarding desire, like feeling good or avoiding shame). Many psychologists and philosophers find this empirical claim false or at least not universally true. But ethical egoism doesn’t depend on that being true; it says, regardless of how people do act, they ought to act in their self-interest. One could reject psychological egoism (acknowledge we can care for others for their sake) but still embrace ethical egoism (claim we shouldn’t do that, we should only care for others if it benefits us).

In summary, ethical egoism stands apart from most other normative theories by denying any fundamental duty to others. It celebrates self-interest as virtue. While few mainstream philosophers advocate pure egoism as a full ethical theory (due to its conflicts with common moral intuitions about fairness and concern for others), it’s an important position to understand – especially since in real-world decision making, people often behave egoistically, raising questions about whether that’s morally acceptable or not.

(Beyond utilitarianism and egoism, there are other specialized consequentialist theories, but in an expanded overview these two suffice as key sub-branches. Some additional forms include: altruism – the idea one should act for others’ good exclusively (the opposite of egoism, but this is often just utilitarianism if “others” includes everyone else), or specific-value consequentialisms like prioritizing environmental outcomes (biocentric consequentialism) or artistic value, etc. However, those are less common as standalone moral theories.)

Why Consequentialism? Consequentialist reasoning is very prevalent in policy and everyday choices (we often weigh pros and cons). It appeals to a certain straightforward logic: of course outcomes matter – morality should be about making the world better. Consequentialism’s strength is its simplicity and flexibility: any situation, just calculate and compare outcomes. Its weakness is that this simple calculus can, in some scenarios, override other deeply held moral convictions (like justice or rights). The subsequent theories (deontology and virtue ethics) can be seen as attempts to correct or constrain a purely outcome-driven approach by reasserting the importance of rules or character.

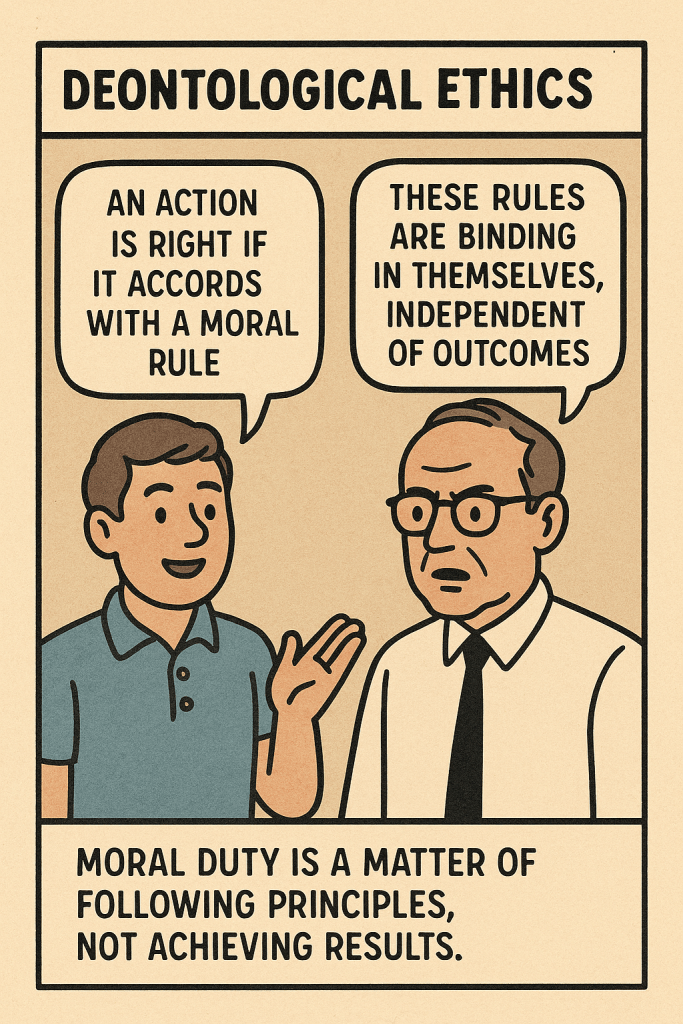

Deontological Ethics (Duty-Based Ethics)

Deontological ethics holds that the rightness or wrongness of actions depends on whether they fulfill our duties or adhere to moral rules, not solely on consequences. The term “deontology” comes from the Greek deon, meaning duty or obligation. In a deontological framework, certain actions are morally required or forbidden in themselves, regardless of the results they produce. Deontologists often stress principles, rules, and the intrinsic moral nature of acts.

Where a consequentialist might say “Lie if it leads to good outcomes,” a deontologist might say “Do not lie, because honesty is a duty,” even if a particular lie could have better results. Deontological theories introduce moral constraints or absolutes: lines that must not be crossed even for good ends.

Key aspects common in deontology:

- Moral rules or laws: There are certain universal rules (e.g., “Do not kill innocents,” “Keep your promises,” “Respect others’ rights”) that define what actions are right or wrong.

- Intrinsic rightness: An action can be right or wrong by its very nature (for instance, murder is wrong because it violates the victim’s right to life, not because of its effect on overall happiness).

- Focus on intentions/principles: Many deontologists evaluate the agent’s intention or the principle they act on (their maxim, in Kantian terms) rather than the outcome. If you do the right thing for the right reason, you are moral—even if things turn out badly.

Deontology includes a range of theories. We’ll cover a few central sub-branches/representative ideas:

- Kantian ethics (duty derived from rationality and universal principles)

- Divine Command Theory (duty as dictated by God’s commands)

- Natural rights theories (duties not to violate fundamental rights of persons)

Kantian Ethics (Immanuel Kant’s Categorical Imperative)

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) is arguably the most influential deontologist. Kant sought a foundation for morality in reason itself. He argued that moral duties are derived from a single rational principle he called the Categorical Imperative (CI). “Categorical” means it applies regardless of one’s desires (unconditional), and “Imperative” means a command. The CI is essentially a universal moral law that rational beings must follow.

Kant formulated the CI in several ways; two famous formulations are:

- Universal Law Formula: “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.” This means: before you do something, imagine if everyone followed the same principle of action. If the action’s guiding rule (maxim) cannot be universalized without contradiction or chaos, then it’s not moral. For example, if your maxim is “I will lie to get myself out of trouble,” universalizing that would mean “everyone may lie to get out of trouble” – but then lies would deceive no one (since no one expects truth) and the concept of trust breaks down, making your maxim ineffective or self-defeating. Thus, lying fails the CI test; it cannot be a universal moral law, so it’s forbidden.

- Humanity Formula: “Act so that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in that of another, always at the same time as an end and never merely as a means.” In simpler terms, this says: never treat people just as tools for your goals; always respect that each person has their own inherent worth (an end in themselves). For Kant, humans (and any rational agents) have dignity and must not be exploited or manipulated, even for good outcomes. This is a strong statement of respect for individual rights and autonomy. For example, using a person as an unwitting test subject to develop a cure (against their will) would be treating them as a mere means, which Kantian ethics prohibits, no matter how beneficial the cure might be for others.

Kantian ethics emphasizes intentions and principle-following. It’s not enough to do the right thing; you must do it for the right reason – namely, because it’s your duty as dictated by rational moral law, not because of expected consequences or personal inclination. If you help someone out of sympathy or for reward, that has no moral worth for Kant; but if you help them because you recognize a duty to help, then it is truly moral.

Example (Kantian duty): Suppose you have a chance to embezzle money at work without getting caught, and you could give that money to feed hungry children. A utilitarian might lean toward embezzling if it does more good. A Kantian, however, would ask: what is the general rule of action here? Perhaps “It’s okay to steal others’ money when I can use it for a good cause.” Could that be universalized? Likely not – if everyone stole whenever they personally judged the cause good, property rights and trust in financial systems would disintegrate; the maxim wouldn’t work universally and people would be using others’ assets as mere means to their own ends. So Kant’s ethics would say don’t steal, period. You have a duty to be honest and respect property, even if your intention is to do charity – because you must respect the other people (in this case, the owners of the money) as ends in themselves. The moral path is to help others through permissible means, not through deceit or theft, no matter how noble your goal.

Kant’s deontology gives us moral absolutes: lying, stealing, killing the innocent are always wrong because the maxims fail the CI or treat persons as mere means. Kant famously argued you should not lie even to a murderer who asks where his intended victim is, because lying cannot be universalized (this rigid stance is widely debated!). Kantian ethics is thus rule-based and inflexible, which is its strength (clear guidance, no loopholes for “well in this case maybe do bad for good outcome”) but also seen as a weakness (what about cases where duties clash or sticking strictly to a rule seems to cause preventable harm?).

Kantian ethics has a profound legacy in the concept of human rights and dignity. The idea that individuals have inviolable rights and must not be treated as mere tools aligns with Kant’s humanity principle. Many contemporary deontologists build on or modify Kant’s framework to accommodate some flexibility or to handle situations of conflicting duties (like telling a lie to save a life).

Divine Command Theory

Divine Command Theory (DCT) is the view that moral right and wrong are determined by the commands of God (or the gods). In its simplest form, it says: an action is morally right if God commands (or wills) it; wrong if God forbids it. Morality is thus grounded in divine authority.

This theory is deontological in the sense that it provides absolute rules (God’s commands) that must be obeyed, regardless of consequences or human opinion. For a devout believer, these commands constitute duties. For example, if a holy scripture or revelation says “Do not commit adultery” or “Give to the poor,” those are moral obligations because God has decreed them. Conversely, acts like theft or murder are wrong because God has prohibited them (e.g., in the Ten Commandments or other religious laws).

Key aspects of divine command theory:

- Moral authority: God is the ultimate legislator of morality. God’s perfect nature or will defines goodness. As one source puts it, for a theist, “the moral acts are those that we would all agree to if we were unbiased, behind a ‘veil of ignorance’” is Rawls’s contractarian view, but “the moral acts are those commanded by God” would be the DCT perspective.

- Obligation through obedience: To be moral is fundamentally to do God’s will. The virtue is in obedience and faithfulness to divine law.

- Objectivity (for believers): It offers an objective foundation (God’s will) so it’s not relative to human culture or individual – though of course different religions have different divine commands reported, which complicates things.

Example (Divine Command in practice): Consider the moral question of honoring one’s parents. A divine command ethicist might point to a scripture like “Honor thy father and mother” in the Bible, and conclude that honoring parents is morally required because God commanded it. Even if someone’s parents are difficult or one might think in purely human terms they don’t deserve honor, a believer could see the duty as non-negotiable due to divine authority. Or take prohibitions like “Do not eat pork” (in certain religious traditions) – those become moral rules for adherents not because of health or consequences necessarily, but solely because God’s law prescribes them.

One famous dilemma related to divine command theory is Plato’s Euthyphro dilemma: “Is an action good because God commands it, or does God command it because it is good?” This raises a potential problem: If it’s good because God commands it, morality seems arbitrary – God could command anything (even cruelty), and it would be “good” just because He said so. On the other hand, if God commands it because it’s good, then goodness is independent of God (God is just recognizing moral truths, not creating them, which contradicts a strong version of DCT). Different theologians and philosophers respond variously: some say God’s nature is good and He wouldn’t command cruelty (so it’s not arbitrary, because God’s nature itself is the standard of good). Others adjust DCT to avoid arbitrariness but maintain that without God, we’d have no reason to be moral.

Divine command theory strongly influences many religious believers’ approach to ethics. It emphasizes obedience, duty, and faith. However, secular ethicists often criticize DCT as not accessible to non-believers and as potentially endorsing problematic things if one believes God commanded them (for example, in scripture God commands Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac – was it morally right for Abraham to be willing to do so? A strict DCT might say yes, because obeying God is paramount, even above normal moral duties like not killing your child).

Regardless of one’s view on its truth, divine command theory underscores how morality is often experienced by people as following a higher law. It clearly falls in the deontological camp: the rightness lies in the adherence to command/duty, not in weighing outcomes.

Rights-Based Ethics (Natural Rights and Human Rights)

Another influential deontological perspective revolves around the concept of rights. Rights-based ethics holds that individuals possess certain moral rights (entitlements) by virtue of their nature (often said to be natural rights) or by virtue of moral or legal conventions (human rights in political context). Morality then consists in respecting these rights – and duties arise as the obligation to not violate others’ rights (and sometimes to aid in securing them).

Natural rights theory is historically associated with philosophers like John Locke (17th century). Locke argued that by nature (given by God, in his view), human beings have fundamental rights to life, liberty, and property. These rights are prior to any social or political arrangement; governments are formed mainly to protect these natural rights. For Locke, violating someone’s natural rights (murdering them, enslaving them, stealing their property) is morally wrong, period – not because of consequences but because it infringes what inherently belongs to that person.

Rights are deontological in that they function as side-constraints on actions. As philosopher Robert Nozick put it, “Individuals have rights, and there are things no person or group may do to them (without violating their rights).” For instance, even if killing one person could save five (a net positive consequence), a rights view would say you cannot kill the one because that violates their right to life. Each person is inviolable. This is aligned with Kant’s idea of treating persons as ends – rights kind of codify that: to treat someone as an end, you at minimum respect their rights (to life, to autonomy, etc.).

Some important features:

- Rights often come in pairs with duties: If X has a right to something (say, freedom of speech), others have a duty not to interfere with X’s speech. A right to life implies others have a duty not to kill you (and perhaps a duty to help preserve your life in some cases).

- Rights can be negative (the right to not be subjected to certain harms or interference – e.g., right not to be assaulted, right to privacy) or positive (the right to receive certain benefits or aid – e.g., some argue there’s a positive right to basic healthcare or education, meaning others/society has duty to provide these).

- Natural rights are considered inherent and inalienable (you cannot be rightfully deprived of them). They often are thought to come from human nature or God. For instance, the U.S. Declaration of Independence (1776) speaks of people being “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights… Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

- Human rights, as used in modern international discourse, are similar but they’re often justified in a more secular way (perhaps grounded in human dignity or needs). They include rights like equality before law, freedom of religion, freedom from torture, etc. These are enumerated in documents like the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Example (Rights in action): Consider a scenario: A government wants to silence a minority religious group because it believes doing so would increase overall social harmony (maybe the majority is uncomfortable with that minority). A utilitarian government might consider doing it if it truly believed it increases net happiness. But a rights-oriented approach would say: “No, people have a right to religious freedom and expression. That right cannot be trampled just because doing so would please the majority. The minority’s liberty is protected.” Similarly, in criminal justice, a rights view emphasizes due process – you can’t just punish an innocent person even if it would scare others into obedience (violating the innocent person’s rights to justice).

Natural law theory, often in the Catholic tradition, is related – it holds that moral principles (including rights) are derived from the nature of humans and the world (as designed by God’s rational order). People have natural inclinations (to life, to procreate, to know truth, to live in society, etc.), and from these a set of natural laws and rights can be deduced. For example, because of the value of life, natural law ethicists say there’s an absolute prohibition on intentionally killing the innocent (just like rights/duty ethics).

Nozick’s libertarian rights theory (1970s) held that individuals have robust rights to life, liberty, and property – so much so that any redistributive taxation beyond minimal necessary for protection is immoral (because it violates property rights). That’s one political extension of deontological rights thinking.

Rights-based ethics vs. Kant: They align heavily – respecting rights is akin to respecting the intrinsic worth of individuals. But rights talk adds a more legalistic or entitlement-focused language. It also allows some pluralism: one can list multiple specific rights that might come into conflict and need balancing.

One challenge in rights ethics is conflict of rights: What if one person’s right seems to infringe on another’s? For instance, one person’s right to freedom of speech vs another’s right not to be slandered – those need delineation. Or a serious one: a fetus’s right to life vs a woman’s right to bodily autonomy (the abortion debate often pits these perceived rights against each other). Deontologists have to find principled ways to adjudicate such conflicts (e.g., which right is more fundamental or if one right is conditional).

In summary, rights-based ethics provides a framework of inviolable protections for individuals, which generate duties for others to refrain from certain actions (or perform certain supportive actions). It’s a cornerstone of many ethical and legal systems worldwide today. It stands opposed to purely outcome-based reasoning: even if violating one person’s rights would benefit others greatly, it’s typically deemed impermissible. This moral stance was clearly illustrated in the earlier-cited Normative Ethics Wikipedia excerpt: rights theories hold that humans have absolute, natural rights which must not be transgressed.

Other deontological theories: Beyond Kant, divine commands, and rights, there are other deontological approaches. For example, W.D. Ross’s prima facie duties: Ross recognized multiple independent duties (fidelity, reparation, beneficence, justice, etc.) that aren’t absolute but generally binding unless they conflict, in which case we must judge which is weightier in context. This is a softer deontology, admitting that sometimes duties must yield to stronger duties. It captures moral common sense that we have many kinds of obligations. Ross’s theory is deontological because it’s about duties rather than max utility, but it’s not rigid absolutism like Kant’s – it requires judgment to balance duties when they clash.

To wrap up deontology: These theories emphasize principle, duty, and the inherent morality of actions and respect for persons, often providing a bulwark for individual rights and ethical rules that should not be broken. They address some shortcomings of consequentialism (like sacrificing individuals for aggregates) but face their own difficulties (like handling tough moral dilemmas where rules conflict or the costs of rule-following seem unbearably high).

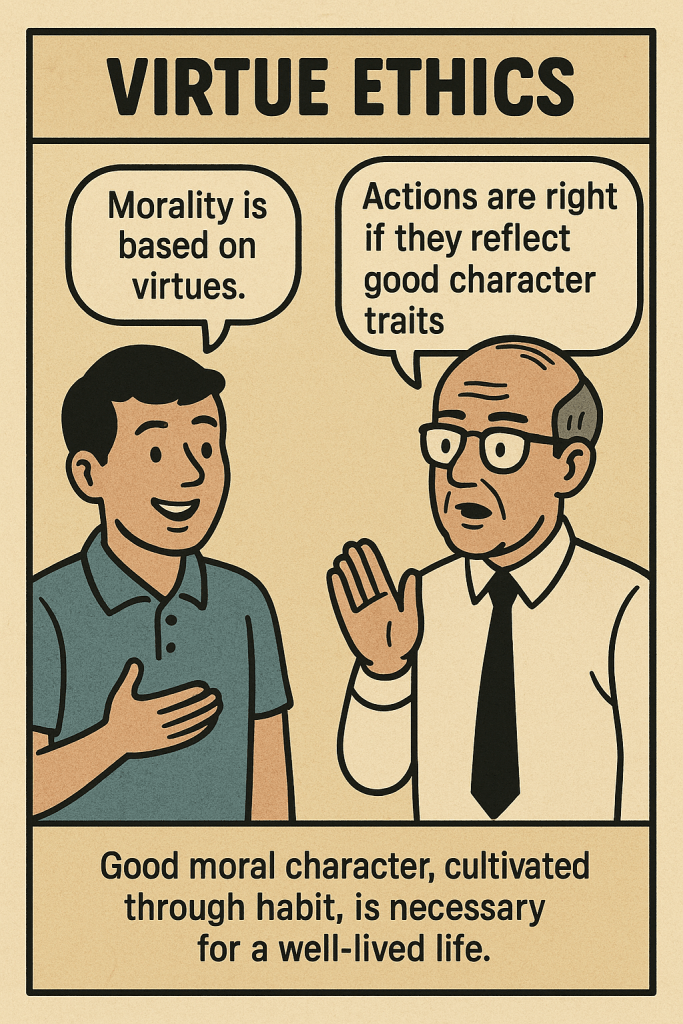

Virtue Ethics

Virtue ethics shifts the focus from rules or consequences to character. It is an approach to normative ethics that emphasizes the virtues or moral character of the person carrying out an action, rather than the ethical status of the act itself (deontology) or its consequences (consequentialism). In other words, virtue ethics asks not “What should I do?” but more fundamentally “What kind of person should I be?”

At the heart of virtue ethics is the concept of a virtue: a trait of character that is morally valuable – such as honesty, courage, compassion, generosity, fidelity, integrity, fairness, self-control, prudence, etc. A virtuous person will tend to do the right things for the right reasons, so by cultivating good character, good actions follow naturally. Likewise, vice (bad traits like cowardice, greed, dishonesty) leads one astray.

The roots of virtue ethics lie in ancient philosophies, especially those of Aristotle in the Western tradition and Confucian thinkers in the Eastern tradition (and also in many others, such as Stoics). We will outline the Aristotelian paradigm as the primary example of virtue ethics, and also mention how other traditions align.

Aristotelian Virtue Ethics

Aristotle (384–322 BCE) in his Nicomachean Ethics presented a systematic virtue ethics. Some key elements of Aristotle’s approach:

- Teleology (purpose): Aristotle believed everything has a purpose or end (telos). For humans, he argued our ultimate end is eudaimonia, often translated as “flourishing” or “happiness” in a deep sense (not just pleasure, but living and faring well as a human). Ethics, for Aristotle, is about how to live a life conducive to eudaimonia.

- Virtue (arete): Virtues are excellent states of character that enable a person to fulfill their purpose and live well. They are developed habits or dispositions to act and feel in certain good ways. For example, courage is a virtue that helps one handle fear and face challenges appropriately, contributing to a good life; temperance is a virtue concerning pleasure and self-control, etc.

- Doctrine of the Mean: Aristotelian virtues are often means between extremes (the famous “golden mean”). Each virtue is a moderate position between two vices of excess and deficiency. For example, courage is the mean between recklessness (excess of fearlessness) and cowardice (excess of fear). Generosity is between prodigality (giving too much or unwisely) and stinginess (giving too little).

- Practical wisdom (phronesis): To apply virtues in real life, one needs practical wisdom – the intellectual virtue that allows one to discern the right mean in the right situation. It’s not a simple formula; it requires experience and good judgment. A virtuous person with phronesis can see what’s the honorable or fitting action in context.

- Holistic character: Virtues are deeply interconnected; truly having one virtue often implies having others, because they form a coherent character aimed at the good life. Aristotle thought you need all the main virtues to fully flourish.