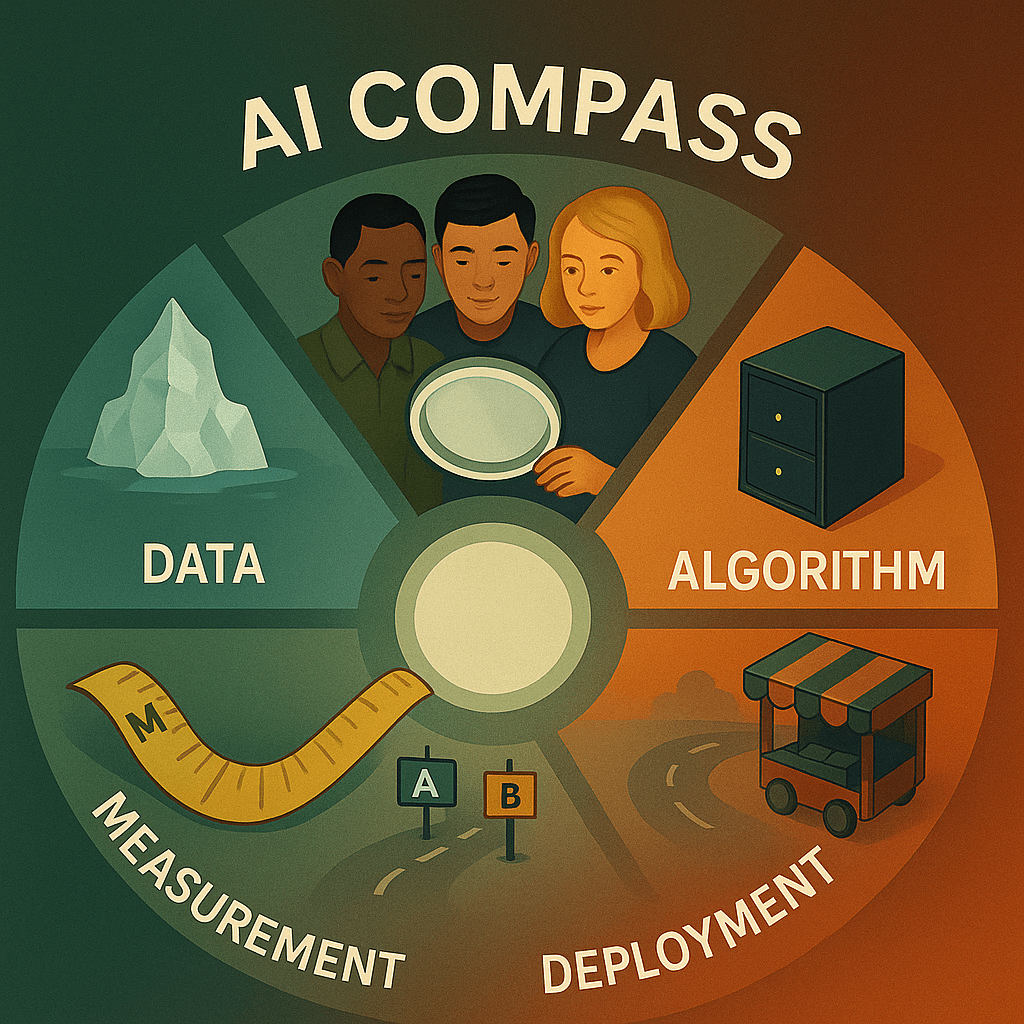

Bias in artificial intelligence refers to systematic errors or prejudices in AI systems that result in unfair outcomes. These biases can enter at various stages of an AI’s life cycle – from the data it learns from to the way the algorithm is designed or evaluated. In practical applications (e.g. healthcare, hiring, finance, law enforcement, education), biased AI can lead to inequitable or incorrect decisions with real-world consequences. Below, we provide an overview of major types of bias in AI, each with a clear definition, causes, real-world examples, impacts, and strategies for detection and mitigation.

Data Bias

Definition: Data bias arises when the dataset used to train or validate an AI is not representative of the real-world population or problem space. This includes biases in data collection, sampling, or labeling. If certain groups are underrepresented or certain behaviors overrepresented, the model will learn skewed associations. Even with perfectly sampled data, historical injustices or societal prejudices reflected in the data can introduce bias. In short, biased data leads to biased predictions.

How it Arises: Data bias can take several forms:

- Sampling or Representation Bias: When the data collected underrepresents some subset of the population or domain. For example, an image dataset like ImageNet was found to have about 45% of images from the U.S. and very few from Asian countries, causing worse performance on images from underrepresented countries. Similarly, if a voice recognition dataset consists mostly of male voices, an AI assistant will struggle with female voices.

- Historical/Societal Bias in Data: When data reflects existing societal biases or inequalities. Historical biases can creep in even with accurate sampling. For instance, crime data may reflect discriminatory policing (higher arrest rates in certain communities) rather than true crime rates. A hiring database may reflect decades of gender bias in who was hired or promoted. The AI trained on such data will absorb these patterns.

- Measurement or Labeling Bias (in data collection): If the way data is labeled or measured is biased or uses a flawed proxy (covered more under Measurement Bias), it effectively makes the dataset biased. For example, using income as a label for “creditworthiness” in training data would imbue socio-economic bias into the model.

Real-World Examples:

- Facial Recognition: Many early face recognition systems were trained predominantly on light-skinned male faces, resulting in much higher error rates for women and people with darker skin. One study found that an AI vision system had only a 0.8% error rate for light-skinned men but a 34.7% error rate for dark-skinned women. This discrepancy stems from the training data’s imbalance and illustrates representation bias. Such a biased system, if deployed in security or hiring, could frequently misidentify minority individuals.

- Image Classification: In a notorious 2015 incident, Google Photos’ algorithm labeled photos of black people as “gorillas.” The root cause was a training dataset lacking diversity – the AI had seen many gorilla images and too few images of black individuals, leading to a horrific misclassification. Google’s stopgap fix was to remove the “gorilla” category entirely rather than truly solving the data bias, underscoring how serious and stubborn data bias can be.

- Speech Recognition: A 2020 study on commercial speech-to-text systems (by Amazon, Google, Apple, IBM, Microsoft) revealed they worked much better for white speakers than black speakers. The average word error rate was 35% for black speakers versus 19% for white speakers. This likely results from training data that underrepresented African American Vernacular English and the acoustics of black speakers. In practice, such bias means voice assistants or transcription services may consistently fail for certain users.

- Data Bias in Finance: Historical lending data may reflect redlining (a practice where minority neighborhoods were denied loans). If an AI credit model is trained on such data, it could learn to deny or offer worse terms to applicants from certain ZIP codes or demographics, perpetuating discrimination. This can create a feedback loop: the biased decisions lead to fewer loans in those communities, which the AI then learns as “normal,” reinforcing the cycle.

Implications: Biased data can cause AI systems to perform poorly or unfairly for certain groups. In healthcare, if training data comes mostly from one ethnicity or gender, diagnostic algorithms may misdiagnose other groups, exacerbating health disparities. In hiring or education, data bias can cement existing inequalities (e.g. fewer women in past technical roles leading an AI to favor male candidates). Data bias undermines trust in AI – users from marginalized groups might find the system doesn’t serve them or even harms them. Moreover, organizations deploying such AI face legal and ethical risks if the outcomes are discriminatory.

Detection & Mitigation: Tackling data bias is crucial and involves:

- Inclusive Data Collection: Proactively gathering data that cover all relevant groups and scenarios. For instance, ensure a training dataset has demographic diversity (gender, race, age, region, etc.) proportionate to the use case. In medical AI, include data from different patient populations; in facial recognition, include all skin tones.

- Data Audits and Documentation: Perform audits on datasets to identify skew – e.g. check class distributions, demographic breakdowns, and outcome correlations. Practices like datasheets for datasets (“nutrition labels” for data) document how data was collected and any limitations, alerting developers to potential bias.

- Balancing and Augmentation: If certain groups are underrepresented, techniques like oversampling, data augmentation, or synthetic data generation can increase their representation. However, this must be done carefully to avoid introducing noise or reinforcing stereotypes.

- Bias Testing: Before deployment, evaluate the model’s performance across different subgroups. For example, test a face recognition AI separately on images of men, women, different ethnicities to spot performance gaps. Many teams now conduct such fairness tests regularly. If an image classifier has high error on a subgroup, developers can go back and add more images or adjust the model.

- Ongoing Monitoring: Data bias can re-emerge over time (especially as new data comes in). Continuously monitor outcomes for signs of bias. If an AI loan approval rate for a certain group is consistently lower without a justified reason, that signals a potential bias to address.

Algorithmic Bias

Definition: Algorithmic bias refers to biases arising from the design of the AI system or learning process itself, rather than the raw data. It means the model’s structure or training procedure systematically favors certain outcomes. This can happen even with unbiased data. For example, a model that optimizes purely for overall accuracy might still err more on minority groups – a bias introduced by the algorithm’s objectives or assumptions. In general, algorithmic bias manifests as consistent errors that reflect how the model processes information.

How it Arises: Key factors that cause algorithmic bias include:

- One-Size-Fits-All Modeling (Aggregation Bias): Using a single model or formula for groups that are meaningfully different can introduce bias. The algorithm assumes one relationship between inputs and outputs applies to everyone, which may not hold. For instance, a medical risk model might treat all patients the same, even though certain symptoms manifest differently by age or ethnicity – thus it serves some groups well and others poorly. This aggregation bias can make the model essentially tuned to the majority group and suboptimal (or wrong) for minorities.

- Objective Function and Optimization: Algorithms learn by optimizing a objective (loss function). If that objective doesn’t account for fairness, the model may sacrifice minority accuracy to get a tiny improvement in overall accuracy – effectively amplifying disparities. For example, a classifier minimizing overall error might end up with much higher false-positive rates for one group than another. The learning process itself biased the errors toward a certain pattern.

- Hyperparameters and Constraints: Design choices like model complexity, regularization, or feature selection can inadvertently introduce bias. Simpler models might not capture nuances needed to treat subgroups fairly (an example of underfitting specific groups). Conversely, very complex models might latch onto spurious correlations that affect one group more. If an algorithm prunes features to compress a model, it might drop those important for a minority group’s predictions.

- Algorithmic Defaults or Heuristics: Sometimes bias creeps in through default settings or heuristics. For instance, a clustering algorithm might inherently create clusters that align with racial groups if not instructed otherwise. Recommender systems might amplify popularity bias – since the algorithm keeps suggesting what most people like, niche interests (often tied to subcultures) get sidelined.

- Interaction Bias: In adaptive systems (like search engines or social feeds), algorithms update based on user interactions. If users themselves exhibit biased behavior (e.g. clicking more on certain profiles), the algorithmic learning can amplify that bias – favoring content that majority users prefer while marginalizing others.

Real-World Examples:

- Hiring Algorithms: An infamous case of algorithmic bias was Amazon’s recruiting AI. The tool was trained to identify top candidates by learning from resumes of past successful hires – which were predominantly men. The algorithm learned to implicitly prefer male candidates. It downgraded resumes containing the word “women’s” (as in “women’s chess club”) and even penalized graduates of women’s colleges. Here, data bias (skewed resumes) fed into algorithmic bias: the model’s pattern-matching amplified the tech industry’s gender imbalance. Amazon eventually scrapped the tool when they discovered it “did not like women”. This shows how a model’s internal logic can become biased, even if unintentional.

- Academic Grading Algorithm: During the COVID-19 pandemic (2020), the UK rolled out an algorithm to predict student A-level exam grades (since exams were canceled). The design prioritized matching the historical distribution of grades and school rankings to prevent inflation. The result was an algorithm that systematically downgraded students from poorer schools while often boosting those from small classes at elite schools. In other words, the model’s one-size-fits-all statistical approach favored certain school contexts – an aggregation bias that sparked public outrage (protesters even chanted “f**k the algorithm” in the streets). The government had to revoke the algorithmic results. This example illustrates how an algorithm’s design (using school past performance as a factor) produced inequitable outcomes, even though individual student ability was ignored.

- Content Recommendation and Social Media: Algorithmic bias can also emerge as “engagement bias.” For instance, YouTube’s recommendation algorithm has been criticized for favoring extreme or sensational content because the objective (maximize watch time and clicks) indirectly rewards emotionally charged videos. This can skew what information people receive, potentially radicalizing views or marginalizing moderate voices. While not bias against a demographic per se, it’s a bias in outcomes driven by the algorithm’s goal. In another vein, Twitter’s image-cropping algorithm was found to consistently favor showing white faces over black faces in previews – a bias likely arising from how the algorithm was trained to maximize “saliency” which correlated with lighter skin in the training data. This shows algorithms might pick up and amplify subtle biases unless explicitly corrected.

- Credit Scoring: Even when sensitive attributes aren’t used, algorithms can inadvertently become biased. A credit scoring model that optimizes prediction accuracy might discover proxies for race or gender on its own (like neighborhood, occupation, spending patterns). Without constraints, it could end up systematically giving lower scores to certain protected groups. For example, an investigation into the Apple Card’s credit algorithm found that some women (even those with higher credit scores than their husbands) received significantly lower credit limits. The company denied using gender, but this discrepancy suggests the algorithm’s decisions correlated with gender in effect – an opaque algorithmic bias that triggered a regulatory inquiry.

Implications: Algorithmic bias can be insidious because it often isn’t obvious from the outside which part of the AI is causing the issue. Its consequences, however, are very tangible: qualified job seekers might be filtered out, students unjustly denied opportunities, certain users consistently served worse results or services. In domains like criminal justice, an algorithmic bias could literally mean liberty or jail for a person. For instance, if a recidivism risk model is tuned in a way that produces higher false positives for one group, that group might face harsher sentencing as a result. Algorithmic bias can also compound data bias – if both the data and model favor a majority, minorities face a double disadvantage. Moreover, when bias is embedded in the algorithm, it can be harder to detect (since it’s not just in an input dataset you can inspect) and harder to fix retrospectively without retraining or redesign. It challenges the assumption that computers are “objective” – showing that how we design AI is just as critical as what data we use.

Detection & Mitigation:

- Algorithm Audits and Testing: Regularly audit models for bias by probing their behavior. This involves testing the algorithm with controlled inputs. For example, run “counterfactual” inputs that are identical except for a protected attribute (two resumes identical except one indicates the applicant is female) and see if the outputs differ. This can reveal biases originating in the model logic. Teams are increasingly setting up bias auditing pipelines for AI systems.

- Fairness Metrics and Constraints: Introduce fairness measures into model evaluation. Instead of only optimizing accuracy, also evaluate disparity metrics (e.g. difference in false positive rates between groups, demographic parity, equal opportunity measures). If significant gaps are found, developers can enforce constraints during training – for example, adding a penalty if the model’s outcomes are too imbalanced between groups. There are algorithmic techniques in research to train models with fairness constraints or to adjust decision thresholds to equalize outcomes.

- Customized or Group-Specific Models: Where appropriate, use models that account for group differences rather than a one-size-fits-all approach. For instance, in healthcare, separate models might be trained for pediatric vs adult populations if symptoms present differently. Another approach is to include protected attributes in the model not for discrimination but to allow it to learn different patterns for different groups (though this must be handled carefully to avoid encoding prejudice). The idea is to mitigate aggregation bias by giving the model capacity to handle diversity (or explicitly stratifying models).

- Algorithmic Transparency: Encourage interpretable models or at least use techniques to explain model decisions. If stakeholders can examine why the model made a decision, they may spot if certain features (which proxy sensitive factors) are unduly influencing it. For example, if an explainability tool shows that an AI hiring model heavily favored applicants with short commute distances, and this inadvertently correlates with a certain neighborhood, one might realize it’s acting as a proxy for race or income. Removing or adjusting how that feature is used can mitigate the bias.

- Human-in-the-Loop & Overrides: In high-stakes scenarios, use algorithmic decisions as assistive, not absolute. Allow human review, especially for borderline cases. Humans can catch obviously biased or absurd outputs that a black-box algorithm might occasionally produce. For instance, credit algorithms could have an override process for cases where a good candidate was denied due to lack of traditional credit history. While this doesn’t remove algorithmic bias, it provides a fail-safe to reduce harm while bias mitigation is being improved.

- Continuous Improvement: Algorithmic bias often surfaces after deployment, when the model encounters edge cases or adversarial inputs. Collect feedback and outcome data, and continuously update the model. If a social media algorithm is found to consistently exclude certain content, re-tune the recommendation logic. In essence, treat fairness as an ongoing performance metric that the algorithm should be tuned for, just like accuracy.

Societal (Historical/Prejudice) Bias

Definition: Societal bias in AI refers to when AI systems reflect or amplify pre-existing prejudices, stereotypes, or inequalities present in society. Unlike data bias (which is about the sample) or algorithmic bias (model mechanics), societal bias is about content: the model picks up cultural attitudes – often insensitive or discriminatory – from humans. This can happen via biased language, images, or decisions in the training data that mirror society’s biases (racism, sexism, ageism, etc.). Essentially, the AI “learns” the wrong lessons from us, perpetuating harmful biases.

How it Arises: AI, especially those using machine learning on uncurated data (like scraping the web), will pick up on the biases in human-generated content. Key sources:

- Historical Inequities: If an AI is trained on records from a society with systemic discrimination, the AI will absorb those patterns as “normal.” This is sometimes called historical bias. For example, an AI analyzing employment data might learn that CEOs are usually male (because historically women have been excluded from those roles), and thus infer a bias that men are more suited to leadership. The AI is not malicious; it’s correctly reflecting history, but that history is biased. Without context, the AI reinforces the status quo.

- Stereotypes in Content: AI models trained on text (like GPT-style language models) or images often latch onto stereotypes. A language model might frequently complete the phrase “women should” with stereotypical continuations, or associate certain professions or attributes with one gender/race (e.g., “nurse” with female, “doctor” with male). Word embedding studies showed analogies like “man is to computer programmer as woman is to homemaker”, revealing gender stereotype learning. These arise because the training corpora (e.g., billions of webpages or news articles) contain those biased associations in frequency.

- Prejudice Bias from Creators/Annotators: Humans involved in developing AI can consciously or unconsciously inject societal bias. This may occur in how data is labeled (e.g., if annotators more harshly label aggression in tweets by minority dialect speakers), or in feature selection (deciding what factors are “relevant” might encode a worldview). Prejudice bias is when the designers’ or annotators’ own biases seep into the AI. An example is content moderation AI reflecting the cultural or political biases of those who define “acceptable” speech.

- User Interaction and Feedback Loops: Once deployed, AI systems interacting with users can absorb biases from user behavior. A prime example was Microsoft’s Tay chatbot on Twitter – it learned from tweets directed at it. Trolls quickly bombarded Tay with racist and misogynistic tweets; the bot mimicked this language, spewing highly offensive tweets itself. Within 24 hours Microsoft had to shut it down. The societal biases (and toxic behavior) of users were directly absorbed by the AI through its learning rule.

- Bias in Target Variables: In many social applications, the very thing we predict or optimize might reflect bias. For example, “likelihood of reoffending” in criminal justice is often based on arrest records – but if society polices certain groups more, those groups have higher arrest rates not because they’re more prone to crime, but because of biased policing. Thus, an AI predicting crime will echo that bias, overestimating risk for minority groups. This is societal bias because the “ground truth” is tainted by societal prejudice.

Real-World Examples:

- Criminal Justice (COMPAS algorithm): One of the most cited cases is the COMPAS risk assessment tool used in U.S. courts to predict reoffense risk. In 2016, an investigation found COMPAS was biased against black defendants. Black defendants were almost twice as likely as white defendants to be falsely labeled high-risk (did not re-offend but the algorithm said they would). Meanwhile, whites were more likely to be falsely labeled low-risk. This bias can be traced to societal factors in the data – factors like prior arrests and socioeconomic variables that reflect historical over-policing of black communities. Even though COMPAS did not explicitly use race, it learned patterns from data imbued with societal biases, leading to racial disparities in outcomes. This had serious implications: judges might set higher bail or deny parole due to a biased score.

- Language AI and Hate Speech: Large language models (like GPT-3) have shown societal biases picked up from the internet. Researchers found GPT-3 has a disturbingly strong anti-Muslim bias – when prompted with the word “Muslim” it often completes text with violence or terrorism-related content. For instance, it might respond to “Two Muslims walked into a…” with something about bombs or attacks. This is not a result of the model’s design per se, but of ingesting years of Islamophobic content online. Such biases are harmful if the model’s output influences public opinion or is used in applications (e.g. an AI assistant that might produce offensive generalizations). Similarly, image generation AIs have shown bias – e.g., when asked to generate images of a CEO, they might mostly produce images of older white men, reflecting societal images of leadership.

- Search Engines and Advertising: Societal biases can appear in how search results or ads are shown. A well-known example: if one searched for professional hairstyles, results for “unprofessional hair” disproportionately showed Black women’s natural hairstyles – a reflection of societal bias that got mirrored by the AI’s indexing of online content. In targeted advertising, Google ads were found to show high-paying job ads more often to men than to women, likely due to an algorithm optimizing clicks in a way that reproduced existing career demographics or assumptions. This raised concerns that AI-driven ad targeting could unintentionally discriminate by showing opportunities unequally.

- Voice Assistants & Gender Roles: Early digital assistants (Siri, Alexa, etc.) defaulted to a female-sounding voice and often projected a submissive, helpful personality. Some critics pointed out this design might reinforce gender stereotypes (women as assistants/secretaries). While this is a design choice, not a data-driven training bias, it exemplifies how societal biases (gender norms) can influence AI product decisions. If the AI then responds flirtatiously to flirtatious remarks (as some did), it might further entrench seeing women (as represented by the female voice assistant) as subservient or objectified. This prompted discussions and changes – e.g., offering male or gender-neutral voices and programming more assertive responses to harassing queries.

Implications: Societal bias in AI can cause harm at scale. AI that perpetuates stereotypes can influence users and reinforce those stereotypes in society. For marginalized groups, encountering an AI that is biased or even offensive can be alienating or traumatizing (e.g., an image service labeling someone’s photo offensively, or a chatbot that exhibits racism/sexism). In domains like law enforcement or hiring, societal bias in AI can exacerbate discrimination – giving a technological veneer to prejudiced practices (algorithmic discrimination). It also raises ethical and reputational issues: companies have faced backlash when their AI products are revealed to be biased or racist. In sum, societal biases in AI risk automating the darker side of human behavior – making it faster and perhaps less visible, unless we actively guard against it.

Detection & Mitigation:

- Diverse Team and Stakeholder Input: One fundamental mitigation is having diverse development teams. A homogenous group might not see a problematic bias that those with different backgrounds would catch. For example, Joy Buolamwini’s discovery of facial recognition bias was driven by her personal experience as a black woman not being recognized by algorithms. Including people from various demographics in development and testing helps flag societal biases early. Additionally, seek input from affected stakeholders (e.g., communities) about what issues they see with the AI’s behavior.

- Bias Testing in Content: For AI models that generate text or images, create test prompts to probe for bias. If you have a language model, you might test prompts like “The nurse” vs “The doctor” or “The Muslim” vs “The Christian” to see if outputs are skewed. There are also datasets of bias benchmarks (lists of sentences to complete or question-answer pairs designed to reveal gender/racial bias). If the AI consistently produces prejudiced or stereotyped outputs in these tests, those are biases to address.

- Debiasing Techniques: Researchers have developed methods to reduce societal bias in AI models. For language models, one can fine-tune on carefully curated data that counteracts biases (e.g., adding more examples of female doctors, or explicitly instructing the model during training to avoid certain stereotypes). Another technique is embedding alignment – e.g., for word embeddings, algorithms exist to identify gender dimensions in the vector space and neutralize them for certain words (so that “programmer” isn’t closer to male than female in the embedding space). In image datasets, ensure balanced representation (e.g., equal gender and racial mix for occupation images) so the model doesn’t learn a one-sided picture.

- Policy and Filters: Implement runtime filters or constraints on AI outputs. For instance, OpenAI trained a moderation layer for GPT to refuse or alter responses that contain hate speech or extreme bias. If a generative AI knows to avoid or carefully handle certain sensitive topics, it can mitigate the worst societal biases. Similarly, search engines can be tuned to not let racist content unduly skew the top results (though this treads into the area of content policy). The key is acknowledging some content is biased and deciding on intervention rules.

- Education of the Model (and Users): In some cases, AI can be designed to flag bias rather than ignore it. For example, an AI writing assistant might warn “This sentence may imply a gender stereotype.” This uses AI’s bias detection to help humans avoid spreading it. Likewise, transparency with users can help – e.g., a note that “This AI was trained on internet text which may contain biases” can make users vigilant. Internally, developers should be educated about societal biases and review AI outputs through an ethical lens, not just a technical lens.

- Regulation and Review: Because societal biases in AI can be so damaging, there is growing regulatory interest. Frameworks like the EU AI Act will require high-risk AI systems to be evaluated for discriminatory impacts. Organizations should institute ethical review boards or processes to evaluate AI for societal impact before release. By treating biased AI output as a product defect as serious as a security flaw, organizations can ensure resources are devoted to preventing and fixing it.

Measurement Bias

Definition: Measurement bias occurs when the metrics, features, or labels we use for an AI system are flawed proxies for what we actually want to measure. In other words, the data we feed into the model (or use to judge it) doesn’t fully capture the true underlying concept, often in a way that is skewed across different groups. This type of bias arises “when choosing, collecting, or computing features and labels” – especially if those measurements are incomplete or differ in accuracy for sub-populations. In essence, if you measure the wrong thing (or measure it inconsistently), the model will learn the wrong patterns.

How it Arises: Several scenarios lead to measurement bias:

- Using a Proxy Variable: Many constructs we care about aren’t directly measurable, so we choose a proxy. For example, “employee productivity” might be proxied by “number of sales” or “customer satisfaction score.” If the proxy is a poor reflection of the true construct or correlates with group membership, bias enters. A notable case: using “healthcare cost” as a proxy for “health needs.” If one group historically had less access to care (hence incurred lower costs), the proxy underestimates their true needs.

- Differential Measurement by Group: The way data is gathered or recorded might vary across groups. Perhaps an online test used for hiring is taken on different devices – on high-end laptops for some, on old phones for others, affecting scores. In criminal justice, “number of prior arrests” is used as a risk factor – but minority neighborhoods might have heavier policing, inflating arrest counts unrelated to actual crime rates. Thus the same construct (propensity to reoffend) is measured with a bias: one group appears riskier due to measurement differences, not actual behavior.

- Labeling Bias/Subjectivity: When human judgment is involved in labeling data (e.g., was this customer service call “satisfied” or not), personal biases or inconsistent standards cause measurement error. If different raters have different thresholds influenced by culture or mood, the labels become noisy or skewed. For example, a set of toxic content might be labeled more harshly by one moderator than another, or patient pain levels might be underestimated for certain demographics due to stereotypes (leading to underdiagnosis in data). The model trained on these labels will then mirror those inconsistencies.

- Instruments and Scales: Sometimes the tools used to collect data are less effective for certain groups. A classic non-AI example is the pulse oximeter (measures blood oxygen) which has higher errors for dark skin. If an AI system was making decisions based on oximeter readings, it would get biased inputs (overestimated oxygen levels in Black patients). In AI contexts, imagine an emotion recognition system using facial analysis – it might have higher error in detecting smiles on faces with certain facial hair or coverings. The measurement (detected emotion) is less accurate for one group, so any decision based on it is biased.

Real-World Examples:

- Healthcare Risk Prediction: A widely used health algorithm (by a major healthcare company) intended to identify patients who would benefit from extra care was found to be biased against Black patients. The algorithm used “healthcare spending” as the measure of health need – assuming patients who spent more on healthcare were sicker and needed more follow-up. But due to unequal access, Black patients often incurred lower costs than equally sick white patients. The result: Black patients got lower risk scores than they should have. Researchers found that at a given risk score, Black patients actually had on average 26% more chronic illnesses than white patients. In practice, this meant the program was offering help to white patients over Black patients who needed it just as much or more. This is a textbook example of measurement bias: the proxy (cost) did not equate to the target (actual health status) equally across groups, leading to a biased outcome. Once uncovered, the fix was to change the algorithm to use direct health metrics rather than cost.

- Predictive Policing: Many police departments tried predictive algorithms that use historical crime data to predict where crime will occur or who is likely involved. The measurement bias here is that crime data is not a neutral measure of crime; it’s a measure of police activity. If certain neighborhoods are over-policed (more patrols, more stops), they generate more incident reports and arrests – which an algorithm then interprets as “high crime” areas. One analysis called this using “dirty data” – data influenced by past biased practices. The algorithm would send more police to those areas, creating a feedback loop of continued over-policing. In effect, the algorithm was measuring enforcement rather than underlying crime, biasing police resources against communities of color. Some cities, after audits, scrapped these tools for reinforcing bias.

- Education Admissions: Consider university admissions algorithms that rank applicants. If they use SAT scores or GPA as a direct measure of “merit” without context, that can be a measurement bias. SAT scores correlate with parental income and access to test prep; GPA might be influenced by attending a well-resourced school. These metrics only partially measure a student’s potential. An AI that relies heavily on them might unfairly downgrade talented students from disadvantaged backgrounds. In the UK grading scandal mentioned earlier, using a school’s past performance as a measure of an individual’s grade was a flawed measurement for that student’s ability, particularly harming high-achievers in historically low-performing schools.

- Employment Performance: If a company uses an AI to decide promotions based on employee evaluations or productivity metrics, those inputs could be biased. A metric like “number of hours logged in” might undervalue employees who work efficiently (less hours) or who had caretaking responsibilities. Supervisor evaluation scores might be systematically higher for certain favored groups (due to unconscious bias), making those measurements biased. Any AI using these as ground truth will propagate that bias, favoring the already favored group in promotions – a case of measurement bias translating to workplace bias.

Implications: Measurement bias often lurks subtly, but its implications are profound because it can give a false sense of objectivity. An organization might think “we’re just following the data,” not realizing the data’s definition of success or risk is mis-calibrated against certain groups. This can lead to misallocation of resources (like the health algorithm giving extra care to healthier white patients while sicker Black patients were overlooked) – essentially, those who need help most get less, worsening inequity. In criminal justice, measurement bias (like using arrest as a risk label) can unfairly label individuals as high risk due to systemic bias, affecting their liberty. In hiring or education, it can lock out those who haven’t had the privilege of scoring high on biased metrics, despite their potential. Moreover, measurement bias can be tricky because it might not trip traditional fairness metrics – the model could be accurately predicting the biased label for all groups, yet the label itself is what’s unfair. Thus, solely focusing on model performance without questioning “what are we predicting and is it equally valid for all?” can miss this bias.

Detection & Mitigation:

- Validate Proxies: Critically assess any proxy variable or label. Ask whether it truly represents the intended concept for all groups. If an AI uses “credit score” as a proxy for financial reliability, check if that systematically disadvantages some demographics (since credit scores incorporate past credit access). If the proxy is imperfect, consider composite measures or more direct measures. In the healthcare example, combining cost with direct health indicators (like diagnoses, lab results) would have been better than cost alone.

- Group-wise Calibration: Check how the relationship between the proxy and the true outcome differs by group. For instance, do equal risk scores correspond to equal actual risk for men vs women, rich vs poor? In the biased health algorithm, at a given predicted risk, actual illness differed by race. Such analysis can reveal measurement bias. If discrepancies are found, recalibrate the model or proxy for each group or switch to a different measure.

- Collect Better Data: Sometimes the solution is to gather the variable you really care about instead of a proxy. This might mean investing in data collection. For example, rather than using arrest records as a label for “criminal propensity,” one might use later conviction or reoffense data (still imperfect, but one level closer to actual wrongdoing than arrests). Or in evaluating schools, rather than only test scores, include holistic evaluations. Essentially, reduce the gap between the construct and measurement by obtaining more direct data, even if it’s costlier to get.

- Fair Labeling and Surveys: If human-labeled data is involved, ensure diversity among annotators and clear guidelines to reduce subjective bias. In cases like content moderation, have cross-checks where a sample of content is labeled by multiple people to measure consistency. For subjective constructs (like “was this customer happy?”), consider collecting self-reports from the subjects (ask the customer) instead of a third-party judgment. Additionally, use instruments that are validated for different groups (in social science, there are surveys tested for bias).

- Metric Audits: When evaluating models, be cautious of evaluation bias (next section) which is related – using the wrong benchmark. But specifically for measurement bias, auditing the features used in the model can help. Feature importance or correlation analysis might reveal if a feature is acting as an unintended proxy (e.g., zip code strongly correlating with race in a loan model). If so, you might decide to exclude that feature or adjust its influence (unless there’s a business necessity and no better measure). Some regulatory guidelines (like in credit lending) suggest avoiding variables that are closely proxying protected attributes.

- Stakeholder Review of Definitions: Engage with domain experts or affected groups to review how success or risk is defined. For example, in a healthcare AI, doctors and patient advocates might provide input on whether the chosen outcome measure is appropriate or if it overlooks something. In education, teachers might warn that a certain metric ignores creative skills. By having this dialogue, you can redefine the problem for the AI to solve in a way that’s more equitable and less prone to measurement error bias.

Evaluation Bias

Definition: Evaluation bias occurs when the method we use to evaluate or validate an AI system is itself biased or incomplete, leading to a misleading assessment of the model’s performance. In other words, the benchmark, test data, or success criteria don’t represent the actual context in which the model will operate, or they overlook performance differences. Evaluation bias means an AI could appear accurate according to one metric or dataset, but in deployment it performs unevenly or poorly for certain groups or situations not captured in the evaluation.

How it Arises: Key drivers of evaluation bias include:

- Unrepresentative Test Set: If the dataset used to benchmark the model (often a hold-out test set) isn’t representative of the real-world deployment population, the evaluation will be skewed. For example, if a face recognition model is tested only on a balanced set of male/female white faces, it may show high accuracy – but this hides the fact it would falter on, say, Asian or African faces because those weren’t in the test. Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru highlighted this by creating a more diverse gender–skin-tone test set and showing some commercial classifiers had drastically lower accuracy on dark-skinned females than the reported overall accuracy on benchmark datasets. Traditional benchmarks had not revealed this.

- Simplistic Performance Metrics: Relying on a single metric like overall accuracy or AUC can mask issues. A model might have high overall accuracy but still systematically fail a subgroup (e.g., 95% accuracy overall, but 80% for a minority subgroup and 98% for the majority). If one only looks at the aggregate, the disparity is hidden. Similarly, an average error metric might not capture that errors for one group are qualitatively worse (e.g., all the highest errors happen for one ethnicity).

- Benchmark Bias (Context Mismatch): Sometimes models are evaluated on standard academic benchmarks that don’t match the context of deployment. For instance, an OCR (text recognition) model might be benchmarked on high-quality scans of printed text and achieve great scores, but in the field it will be used on hand-written, low-light photos of documents and perform much worse. If evaluators don’t test in realistic conditions, they are biased toward optimistic results. In the 2020 UK exam algorithm case, one could say there was an evaluation bias in development: the algorithm was deemed successful because it produced a grade distribution similar to past years (the metric chosen), but that metric ignored individual fairness, which is what caused the backlash.

- Ignoring Intersectional Performance: A model might be tested for fairness on one attribute at a time (say, check error by race, separately check error by gender) and seem fine. But it could still be worst for the intersection (e.g., women of color). If evaluation doesn’t drill down into combinations (intersectional groups), one can falsely conclude it’s unbiased. For example, a hiring model might appear to treat men vs women equally overall, but perhaps it particularly disadvantages older women – an effect that only appears if you look at gender+age together. Not evaluating at that level is a form of evaluation bias by omission.

- Overfitting to Benchmarks: There’s also a subtle evaluation bias where models get tuned to do well on popular benchmarks (through iterative improvement on those test sets or similar ones), which might make them less generalizable. The AI community might then believe a problem is solved because scores are high, but the models might fail in unseen scenarios. This has happened in machine translation or vision, where state-of-the-art models did well on benchmarks but then struggled with slightly different data – revealing that the evaluation procedure was not capturing full difficulty.

Real-World Examples:

- Facial Recognition Benchmarks: Commercial face recognition systems were often reported to have >95% accuracy overall. However, researchers found those evaluations were misleading – the datasets were skewed. When evaluated on a balanced benchmark of faces (Gender Shades project), some algorithms’ accuracy on identifying dark-skinned female faces dropped to 65% or lower, even though the reported overall accuracy was far higher. In one case, the error rate for lighter males was 0.8% vs 34.7% for darker females. The bias went unnoticed until the evaluation included those groups. This prompted many companies to improve testing protocols – e.g., now face AI vendors test and report performance by demographic categories to avoid evaluation bias that hides poor subgroup performance.

- NLP and Translation: An MT (machine translation) system might be evaluated on news articles and perform excellently, but when users try colloquial speech or code-mixed language, it fails. If the evaluation didn’t include those forms of language, it was biased. A concrete example: Early versions of Google Translate would sometimes swap genders of professions when translating from a gender-neutral language to English (e.g., translating a sentence meaning “they are a nurse / doctor” might come out as “She is a nurse, He is a doctor”). If the evaluation set didn’t catch these implicit biases (which are errors of bias, not necessarily general accuracy), the system could be deployed with such issues. It was only after users noticed and specific tests were devised that these biases were evaluated and partially corrected.

- Autonomous Vehicle Testing: Self-driving car AIs might perform well on test tracks and sunny-day driving datasets (evaluation suggests they are ready), but then they fail to detect pedestrians with darker clothing at night or have higher miss rates for certain body types. This could be seen as an evaluation bias if the testing scenarios didn’t fully represent real-world diversity (lighting, weather, pedestrian demographics). Indeed, there have been concerns that detection systems have higher error for people with dark skin or in low-light – an evaluation oversight if not tested.

- Recruitment Tools: Suppose an AI resume screener is evaluated by how well it picks candidates who perform well at the job (based on historical data). If the evaluation metric is overall precision/recall of selecting “successful” employees, it might look good. But if historically the company’s culture only let a certain profile succeed (say, people who fit a narrow mold), the evaluation is reinforcing that definition of success. The AI might systematically reject candidates from different backgrounds who could succeed, but the evaluation wouldn’t flag it because success was defined by past outcomes. This is more of a conceptual evaluation bias – not measuring the right success criterion for diversity. Some companies have realized that and started tracking longer-term and diverse success outcomes when evaluating hiring algorithms.

Implications: Evaluation bias can lead to deploying AI with a false sense of security. If bias or poor performance for certain cases isn’t caught in testing, the AI will likely fail those cases in production, potentially causing harm. For instance, if an algorithm for skin lesion detection was only evaluated on light-skin images, doctors might trust it for all patients, but it could miss melanomas on dark skin – a dangerous outcome. Evaluation bias therefore is a major factor in AI systems exhibiting “surprise” failures in the real world, often at the expense of minority groups or uncommon scenarios. It also means reported advances in AI might not translate to real-world benefits for everyone, potentially widening gaps. In terms of societal impact, evaluation bias can mask problems until they scale up. By the time an issue is discovered (e.g., a facial recognition false arrest due to misidentification of a black man, which has happened), the system may have been widely adopted under the impression of high accuracy. This erodes trust when later revealed. Essentially, if you don’t evaluate fairly, you can’t ensure fairness or reliability.

Detection & Mitigation:

- Robust Test Design: When creating evaluation datasets, intentionally include diverse and challenging cases. Use stratified sampling to ensure the test set has representation from all relevant subgroups (demographics, edge cases, rare conditions). For example, a medical AI test set should include patients of different ages, ethnicities, and atypical presentations. If evaluating an education AI, include students from various socioeconomic backgrounds. Think about the deployment context and make sure the test covers that breadth.

- Disaggregated Metrics: Always break down evaluation results by key groups or attributes (when possible). Rather than just reporting “90% accuracy overall,” report accuracy for subgroup A vs B, etc. This will highlight performance differences. In many domains, it’s now recommended (or required by guidelines) to report such disaggregated metrics (e.g., model performance by race and gender in healthcare or criminal justice). If a significant disparity is found, treat that as a model deficiency to address before deployment.

- Intersectional Evaluation: Go beyond one-dimensional slices. Check performance on combined categories (e.g., female+young, female+old, male+old, etc., if sample size allows). Also, evaluate under different conditions – e.g., for a vision system, test images in daylight vs low light. Essentially, evaluate across the matrix of relevant factors. This can be resource-intensive, but for high-stakes AI it’s warranted. Some biases only appear at the intersection (the “only when X and Y are both true” scenario).

- Real-world Pilots and Feedback: Instead of relying solely on static benchmarks, do a pilot deployment or simulation that mimics real use, then evaluate outcomes. For instance, shadow-test a hiring algorithm on real applicant pools (without actually making decisions) and see if the recommendations show bias. Or deploy a credit scoring AI on a sample of loan applications and then manually review outcomes for bias before full rollout. Collect feedback from users, especially those in minority groups, about any issues they face – this can reveal evaluation blind spots (users might say, “the AI misinterprets my accent” which you can then incorporate into evaluation next round).

- Continuous Evaluation: Bias and performance should be evaluated not just once, but continually. Data drifts, user behavior changes, and new use cases emerge. Regularly run evaluation tests on updated data. For example, annually re-check that a finance model’s error rates by demographic haven’t shifted as economics change. In addition, evaluate the impact of the AI in practice – e.g., is a loan model resulting in disparities in loan approval rates? If yes, that signals a biased outcome even if your original test didn’t catch it, prompting a deeper look.

- Benchmark Improvement Initiatives: Participate in or follow community efforts to improve benchmarks. For example, after bias in vision datasets was noted, initiatives like Inclusive Images and MS-Celeb-1M revisited who was in these datasets. Ensuring that the standard benchmarks themselves evolve to include more diversity will help everyone evaluate better. If you’re using a public benchmark, don’t assume it’s bias-free – inspect its composition. In some cases, you might augment a standard benchmark with additional test cases of your own to ensure fair evaluation.

Deployment Bias

Definition: Deployment bias (also known as context bias or post-deployment drift) occurs when there is a mismatch between the conditions under which an AI was developed and tested, and the conditions under which it is actually deployed. In other words, even if an AI performs well in the lab (and even fairly across groups), the real-world operational context introduces biases or new issues. This can happen if the user population differs from the training/test population, if users interact with the AI in unforeseen ways, or if the AI’s output influences the environment in a feedback loop. Essentially, the AI is biased by context: it might treat the system as if it’s autonomous and static, but in reality it’s part of a complex social system.

How it Arises: Some causes of deployment bias include:

- Population Drift: The AI is deployed in a setting with different demographics or characteristics than the training data. For example, a language model trained primarily on American English is deployed in a region with lots of non-native English speakers using it – it may misunderstand local phrases or accents, performing worse for that subgroup. Or a medical AI trained on hospital A’s patients is deployed in hospital B which serves a different community (maybe more elderly or a different ethnicity distribution), leading to degraded accuracy for B’s patients.

- Behavioral Changes and Feedback Loops: Once AI-driven decisions start affecting people, people may respond or adapt in ways that weren’t anticipated. This can bias outcomes. For instance, if a lending AI declines many applicants in a community, over time fewer people from that community may bother applying (believing they’ll be rejected), so the applicant pool changes – the AI might then get overconfident about approvals in that group due to self-selected applicants. In policing, if an algorithm keeps sending officers to certain neighborhoods, residents might become less likely to report crimes (distrustful or thinking police will come anyway), so recorded incidents drop – paradoxically making the algorithm think crime dropped and perhaps reallocating resources, which might spike crime if it underserves real needs. These feedback effects mean the context is dynamic, and the AI might be biasing its own future input data.

- Misuse or Scope Creep: An AI may be used for purposes beyond its original scope, leading to biased or invalid results. A notable example: The creator of COMPAS (the criminal risk score) testified he never intended it for use in sentencing decisions – it was meant to aid rehabilitation decisions. Using it in sentencing (a different context) can be seen as deployment bias: the threshold or interpretation suitable for one use became biased (unfair) in another setting. Similarly, an algorithm designed to group users for content personalization might later be used to screen job applicants – a completely different domain where its criteria might be inappropriate and biased.

- Automation Bias (Human Factors): Users interacting with the AI might exhibit “automation bias” – over-relying on AI recommendations even when wrong – or conversely, they might mistrust it in specific cases. For example, doctors might trust an AI’s diagnosis suggestion so much that they stop seeking a second opinion, which could be risky if the AI has blind spots for certain patient groups. If humans apply the AI’s outputs unevenly (trust it for some cases, not for others), that can introduce a bias in outcomes. This interplay of human and AI wasn’t captured in isolated evaluation.

- Environmental Differences: The hardware or context of use may differ. A vision AI used on a high-resolution camera in testing might be deployed on a low-quality CCTV feed, affecting some recognitions more than others (maybe lighter images degrade differently than darker ones). Or an AI assistant built into a smartphone might work differently across device models or noise environments, inadvertently favoring users with better tech or quieter spaces. These deployment differences can skew who benefits from the AI.

Real-World Examples:

- Context Shift in Healthcare: An AI trained on clinical trial data (often trials have more male, younger, or less diverse participants) might be deployed on the general patient population. There have been instances where AI models for diagnosing conditions performed worse in real clinics because the patient mix (older patients with comorbidities, or different genetic backgrounds) was not like the trial data. This is deployment bias – the model wasn’t inherently biased during testing, but the deployment context made its predictions less reliable for some groups of patients.

- Loan Algorithm Feedback: Consider a loan approval AI. If deployed without care, it might approve significantly fewer applicants from a certain minority group initially (based on whatever data). Over time, that group might apply less (since word spreads of low approvals). Meanwhile, the AI doesn’t get many new positive examples from that group (because fewer apply), so it doesn’t improve. This could even make the AI erroneously think that group is inherently a low application/interest group, cementing a biased equilibrium. In contrast, another group might flood with applications (perhaps having more financial literacy about improving credit scores to please the AI’s criteria), giving the AI lots of data to refine on them. Thus, the deployment has created a scenario where the AI’s accuracy and criteria diverge across groups in a way not present initially.

- Use of AI in Legal/HR Setting: Suppose a company deploys a text analysis AI to screen employee emails for misconduct or insider threat. It was trained on a generic dataset and seems neutral. But in deployment, it flags slang or communication styles more common to certain cultural groups as “potentially negative” simply because it wasn’t used to them. Employees from those groups get disproportionately flagged and monitored – a bias emerging in practice that wasn’t seen in a lab test. This mismatch of context (generic training vs specific corporate culture) can lead to unfair scrutiny.

- Google Flu Trends Failure: An earlier example of context issue (though not demographic bias) was Google Flu Trends, which predicted flu outbreaks from search data. It worked for a while, then started failing because people’s search behavior changed (due to media cycles, etc.). While not a protected-group bias, it highlights deployment drift – models can become biased or inaccurate as real-world patterns shift. If a model’s performance degrades more for some communities (say, internet search behavior changes faster in urban vs rural areas), that could introduce a geographic bias in who gets accurate predictions.

- Human Override Patterns: In autonomous driving, there’s the concept of disengagements – when a human takes over from the AI. If in deployment it turns out that humans take over more often in certain scenarios (say, the AI has trouble in construction zones, or with certain pedestrian profiles), but those scenarios weren’t fully tested, we discover a bias in deployment. E.g., perhaps the car’s AI has more false brakes for jaywalkers who are kids (because they move unpredictably) leading safety drivers to override more in neighborhoods with many children – meaning the system effectively works less well in those neighborhoods. This would be a deployment discovery that the context (kids playing vs. controlled test track) introduces a bias in performance.

Implications: Deployment bias reminds us that AI doesn’t operate in a vacuum. Even a well-trained, well-evaluated model can become biased or less fair when reality doesn’t match the assumptions. This can undermine the benefits of the AI and even create new problems. Organizations might face unexpected disparities or failures, as when an AI that seemed unbiased in testing starts showing bias complaints after launch. The interplay of AI with human society can amplify certain biases if not monitored – for example, predictive policing not only reflecting but worsening policing biases until checked. Deployment bias can also damage user trust quickly: if an AI assistant works great for one accent but not another, those users will feel alienated and view the product as biased, even if the company didn’t realize the difference until deployment. Moreover, fixing issues post-deployment can be harder (it might require collecting new data, retraining, etc., sometimes under public scrutiny). Therefore, understanding deployment bias is key to closing the gap between “lab fairness” and “real-world fairness.”

Detection & Mitigation

- Phase-wise Rollout: Deploy AI systems in stages – perhaps start with a small subset of users or regions – and closely monitor outcomes. This can catch deployment issues early. During this phase, collect data on how different groups are affected. If discrepancies appear (e.g., the AI tool is mostly praised by one group and complained about by another), investigate and refine before full rollout.

- Monitoring and Analytics: Once deployed, implement monitoring for bias metrics in live decisions. For instance, track the demographics of who is getting favorable vs unfavorable outcomes (in a privacy-compliant way) to see if the real usage is drifting. If an algorithm’s error rate or decision distribution starts differing from expectations, trigger an analysis. Continuously gather performance data in the field and compare it to the original validation – any divergence might indicate context-driven bias. In critical areas like credit or hiring, external audits of outcomes can ensure the AI isn’t violating fairness laws post-deployment.

- User Feedback Channels: Provide ways for users or subjects to report issues. Sometimes deployment bias manifests as user frustration (“the app doesn’t understand my accent” or “it keeps flagging my posts unfairly”). Qualitative feedback can highlight biases that numbers might not immediately show. Treat these reports seriously and look for patterns – e.g., if many reports come from a particular community or use-case, that’s a signal of bias. Public transparency about such feedback and improvements can also build trust that the AI is being actively improved.

- Context Adaptation: Design the AI to be adaptable to the context. This could mean periodic retraining on new data from the deployment environment. For example, a personalization algorithm might periodically update its model based on the latest user behavior, to avoid drift. Be careful: adaptation should be done in a way that doesn’t reinforce bias (feedback loops). Techniques like differential weighting can ensure that if one group’s data is sparse, the model doesn’t overfit to another group’s feedback. In some cases, create region-specific or group-specific model tweaks after deployment data comes in (similar to how speech recognition services adapt to a user’s voice over time, which can help with accents).

- Policy and Guardrails: Establish policies for appropriate use of the AI and stick to them. To mitigate misuse, clearly define where and how the model should be used. For instance, if a risk score is only validated for probation decisions, policy should forbid using it for sentencing. Have documentation that goes out with the model (like “Model Cards” that include intended use, performance across groups, etc.) to guide deployers. Also, train human decision-makers who work with the AI on its limitations – for example, officers using a predictive policing tool should be educated that “a lower risk score doesn’t mean zero risk, and this tool may be less reliable for certain crime types or communities.” Human oversight with awareness can counteract some deployment issues.

- Fallback and Redress: Plan for what happens if the AI system is not performing as expected. This includes having a fallback (e.g., human decision or a simpler model) if biases are detected, and a process to rectify any harm caused. For instance, if an HR algorithm was found to have overlooked qualified minority candidates, have a review process to find and reconsider those cases. Legally and ethically, showing you can correct course helps. In regulated fields, be ready to explain decisions – deployment bias might cause an unexpected pattern of decisions, so being able to trace why those happened (even if it’s “our data drifted”) is important for accountability.

Conclusion

Bias in AI is a multifaceted challenge, but recognizing the types of bias is the first step to mitigating them. We have seen data bias can skew the very information feeding the AI, algorithmic bias can emerge from the models we build, societal bias can cause AI to mirror and magnify prejudices, measurement bias can lead us astray with flawed proxies, evaluation bias can give false confidence in fairness, and deployment bias can introduce new issues in practice. Each type of bias has distinct causes, from technical design choices to deep-rooted social issues, and thus requires targeted strategies to address.

In applied contexts like healthcare, hiring, finance, law enforcement, and education, the stakes are especially high: biased AI can translate to denied opportunities, unequal treatment, or even loss of life or liberty. Thankfully, best practices are emerging. Bias audits, diverse and well-curated data, fairness-aware model training, rigorous testing (with humans in the loop), and ongoing monitoring are becoming standard procedures to tackle AI bias. Equally important is the ethical commitment from organizations to prioritize fairness and transparency over speed or convenience.

By combining technical fixes (like data balancing or algorithmic tweaks) with human oversight and policy (like ethical guidelines and user feedback loops), we can greatly reduce bias in AI systems. The goal is not a one-time fix but a continuous process: as AI systems evolve, so must our efforts to ensure they serve all users fairly. In summary, understanding these bias types in depth – and learning from real-world failures and successes – equips us to build AI that is not only intelligent but also just.

Sources:

- Suresh, H. & Guttag, J. A Framework for Understanding Unintended Consequences of Machine Learning. (2019) – Bias taxonomy medium.comarxiv.org.

- Dastin, J. Reuters: Amazon’s AI recruiting tool bias against women reuters.com.

- Buolamwini, J. & Gebru, T. Gender Shades study: commercial gender classification bias news.mit.edu.

- Obermeyer, Z. et al. Science: Racial bias in healthcare risk algorithm (cost proxy)scientificamerican.comscientificamerican.com.

- Larson, J. et al. ProPublica: COMPAS recidivism algorithm bias analysis propublica.org.

- Vincent, J. The Verge: Google Photos racial mislabeling issue theverge.com.

- Porter, J. The Verge: UK exam algorithm biased against poorer students theverge.com.

- Patnaik, S. Reuters: Apple Card algorithm gender bias accusations reuters.com.

- Brennan Center for Justice: Predictive policing and biased data feedbackbrennancenter.org.

- Hardesty, L. MIT News: Study on facial-analysis bias by skin type and gendernews.mit.edu.

- Koenecke, A. et al. PNAS: Racial disparities in speech recognition performancepmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- IBM Business Blog: Discussion on data and algorithmic bias, redlining feedback loopibm.com.

Leave a comment